AI Answer Evaluation Platform Live Now. Try Free Answer Evaluation Now

Effectes of Smoking on Human Health

From sacred rituals among Indigenous peoples to the billion-dollar global tobacco industry, smoking has undergone a striking cultural transformation. What began as a social or ritual practice has evolved into one of the most pervasive public health concerns of the modern world.Cigarette smoke contains an insidious cocktail of over 7,000 chemicals, hundreds of which are toxic, and at least 69 are known carcinogens.

This continuous exposure fundamentally alters human physiology, leading to systemic damage across nearly every organ. According to the World Health Organization (WHO, 2025), tobacco use causes more than eight million deaths each year, including 1.3 million non-smokers exposed to secondhand smoke.

From an anthropological perspective, smoking is not merely a medical issue it is a social phenomenon shaped by culture, economy, and identity. Anthropologists study smoking to understand how individual behaviours are influenced by cultural norms, global trade, and symbolic meaning. This article explores both the biological impacts of smoking on the human body and the sociocultural dimensions that sustain its prevalence.

Smoking as a Biocultural Phenomenon

In anthropology, smoking represents a biocultural practice one that connects biological effects with cultural meanings. Tobacco use has been integrated into ceremonies, rites of passage, and community interactions across many societies. However, industrialization transformed smoking from a communal act into a mass-consumed, commercial habit.

Modern tobacco products contain over 7,000 chemicals, more than 100 of which are carcinogenic (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2024). The act of inhaling these substances initiates a cascade of physiological and pathological effects across nearly all human organ systems.

The Immediate and Long-Term Damage

The effects of smoking are cumulative, beginning immediately upon first inhalation and worsening over time.

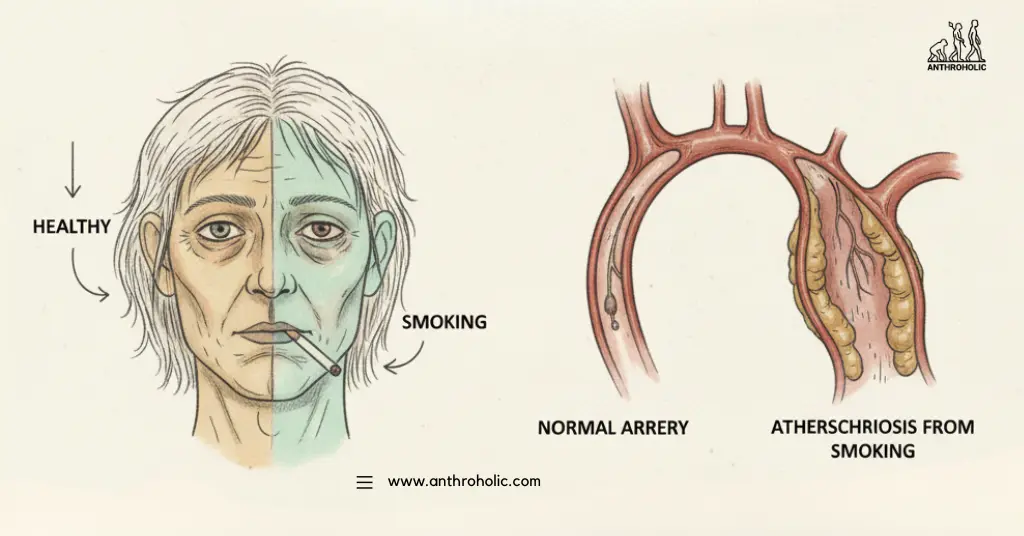

- Cardiovascular System: Smoking is a primary driver of atherosclerosis (the hardening of arteries) and significantly raises blood pressure and heart rate. It damages blood vessel walls, making them prone to plaque buildup, which dramatically increases the risk of myocardial infarction (heart attack) and stroke.

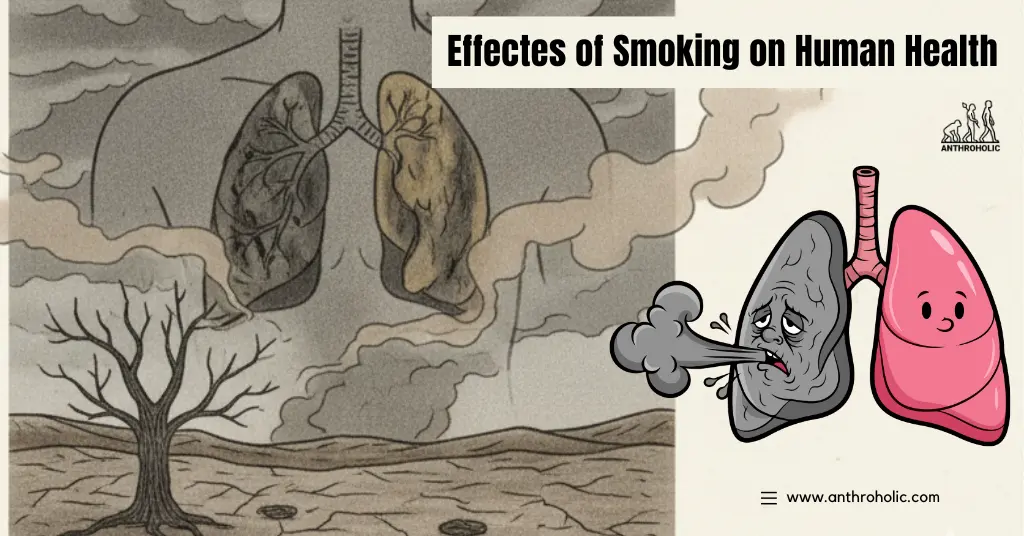

- Respiratory System: The lungs bear the brunt of the assault. Toxins paralyze and destroy the cilia, the tiny hairs that clear mucus and dirt. This leads to chronic inflammation and is the main cause of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), which includes emphysema and chronic bronchitis. The link between smoking and lung cancer is irrefutable, accounting for around 90% of all cases. “Smoking harms nearly every organ of the body and remains the single largest preventable cause of death globally.”

— World Health Organization, 2025 - Cancer Across Systems: Beyond the lungs, smoking is a major risk factor for cancers of the mouth, throat, esophagus, bladder, kidney, pancreas, liver, cervix, colon, and stomach.

- Reproductive and Developmental Health: Smoking impairs fertility in both men and women. For pregnant women, it increases the risk of miscarriage, stillbirth, premature delivery, and low birth weight, leading to long-term health issues for the child.

“Tobacco use is a striking example of the gap between human innovation and biological adaptation. While culturally adopted behaviors can be swift, the pace of biological evolution to mitigate new toxins is glacially slow, leaving modern humans profoundly vulnerable.”

Social‐Cultural Dimensions & Case Studies

- The habit of smoking often serves as a marker of adulthood, gender performance, or resistance to authority in many societies.

- Multinational tobacco companies have influenced smoking cultures globally “health-patterns in Oceania” and other regions have been shaped by global trade and cultural flows.

- A critical anthropology of smoking argues public health discourses may frame smokers too narrowly, missing cultural meaning: “Researching smoking in the new Smokefree: Good anthropological reasons for unsettling the public health grip.”

Passive Smoking

In one large epidemiological review, exposure to second-hand smoke (SHS) was found to increase the risk of ischemic heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes and lung cancer, even among non-smokers.

Implication for Public Health & Anthropology

- Interventions cannot focus purely on individual biology; they must address social networks, cultural norms, industry practices and regulation.

- From an anthropological lens, quitting smoking involves not only physical dependence but also the loss or transformation of cultural roles, peer identity and ritual practice.

Smoking as a Cultural and Social Phenomenon

Anthropology views smoking not merely as an individual habit, but as a deeply embedded biocultural phenomenon. The patterns of tobacco use are shaped by history, cultural norms, social class, and the global political economy of tobacco.

The History of Tobacco Use

Tobacco, originating in the Americas, was used for centuries in ritualistic and medicinal contexts by Indigenous populations. Its use was often highly controlled and symbolic. The rapid global spread after the Columbian Exchange transformed it into a mass consumption product—a process accelerated by industrialization and sophisticated marketing.

The anthropological relevance lies in the shifting meaning of smoking:

- Ritual: Smoking as communion with the spirit world, a prayer, or a symbol of peace (e.g., the pipe ceremony).

- Medicinal: Early beliefs in its curative properties.

- Social Marker: In the 20th century, smoking was heavily marketed as a symbol of sophistication, independence (especially for women), and masculinity.

- Economic Commodity: The rise of powerful multinational tobacco corporations and their impact on global trade, agriculture, and labor.

The Tobacco Industry and Health Disparities

A critical anthropological analysis must include the role of the tobacco industry in perpetuating the health crisis. Their targeted marketing has historically focused on vulnerable groups, including adolescents, low-income communities, and populations in developing nations. People Try Take Weed

This highlights significant health disparities. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), over 80% of the world’s 1.3 billion tobacco users live in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where the burden of tobacco-related illness is compounded by limited access to healthcare.

Addiction and the Biopsychosocial Model

Nicotine, the psychoactive substance in tobacco, is highly addictive. The anthropological perspective integrates the biological compulsion (the neurochemistry of addiction) with the psychological and social factors that initiate and sustain the habit the biopsychosocial model.

Why People Start and Continue

- Social Learning: Observing peers, family members, or media figures smoking normalizes the behavior.

- Stress and Coping: Nicotine is often used as a self-medication strategy to manage stress, anxiety, or depression.

- Peer Group Affiliation: Smoking can act as a social lubricant or a badge of belonging, particularly in adolescent groups where identity formation is paramount.

- Economic Factors: The affordability and accessibility of tobacco in certain regions override health warnings.

We could explore this concept further in our piece on the Anthropology of Addiction.

The Crisis of Secondhand Smoke

The health effects of smoking extend far beyond the individual user, posing a serious ethical and public health challenge in the form of Secondhand Smoke (SHS), or Environmental Tobacco Smoke (ETS).

- SHS is classified as a human carcinogen, containing the same toxic chemicals as smoke inhaled by the smoker.

- In adults, SHS exposure increases the risk of heart disease and lung cancer.

- In children, SHS exposure is a major cause of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS), acute respiratory infections, ear problems, and asthma attacks.

Statistical Insight: Data consistently shows that millions of non-smokers die each year from exposure to secondhand smoke, underscoring the collective, societal impact of this personal habit.

Policy, Intervention, and the Future

Effective intervention requires a multi-pronged approach that addresses biological addiction, social norms, and economic drivers. Public health anthropology plays a crucial role in designing culturally appropriate interventions.

- Taxation and Pricing: Increasing the price of tobacco products is one of the most effective ways to reduce consumption, especially among youth and low-income groups.

- Smoke-Free Laws: Implementing 100% smoke-free public places and workplaces is key to protecting non-smokers and denormalizing the behavior.

- Graphic Warnings and Advertising Bans: Countering industry marketing with strong, image-based warnings and comprehensive bans on tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship.

A study in The Lancet noted the critical role of social and legislative change: “The decline in smoking prevalence in high-income countries demonstrates that the collective will, supported by strong policy, can successfully challenge deeply entrenched social habits.”

A Biocultural Imperative

The effects of smoking on human health represent a profound biocultural tragedy. It is a health crisis born from the complex interaction of a naturally addictive plant, the mechanics of modern industry, and the power of cultural adoption. As anthropologists, we recognize that to effectively combat this global epidemic, clinical efforts must be buttressed by an understanding of the historical, social, and economic forces that put cigarettes in the hands of billions.

The challenge remains: how to shift cultural norms and dismantle the global structures that profit from a product designed to harm. The answer lies in holistic, culturally sensitive, and aggressive public health policy.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Is the risk from smoking reversible?

A: Yes, the human body exhibits remarkable capacity for recovery. Quitting smoking can begin to reduce the risk of heart disease almost immediately. Within 2 to 5 years, the risk of stroke is reduced to that of a non-smoker, and within 10 years, the lung cancer death rate is about half that of a continuing smoker.

Q2: How does smoking affect mental health?

A: While many smokers use nicotine to cope with anxiety or depression, smoking can actually worsen mental health over time. Nicotine withdrawal mimics anxiety, creating a vicious cycle of dependence. Research shows that quitting smoking is associated with reduced depression, anxiety, and stress, and improved positive mood and quality of life.

Q3: What is the primary difference between cigarette smoking and vaping (e-cigarettes) concerning health?

A: Vaping introduces different risks. While e-cigarettes typically do not contain the thousands of combustion-related toxins found in cigarette smoke, they do contain nicotine (which is addictive) and other chemicals, heavy metals, and flavorings that can be harmful to the lungs. Long-term health consequences are still being studied, but it is not risk-free, especially for non-smokers and youth.

Q4: Why are health campaigns often less effective in lower socioeconomic groups?

A: Health campaigns sometimes fail to account for the unique stressors and priorities of lower socioeconomic groups. Smoking rates are often higher due to greater daily stress, targeted industry marketing, lack of access to effective cessation resources, and the fact that for some, smoking is an embedded social norm or an affordable, accessible coping mechanism. Interventions must be tailored and comprehensive.

References

- Cleveland Clinic. (n.d.). Smoking: Effects, risks, diseases, quitting & solutions. Retrieved from https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/17488-smoking Cleveland Clinic

- Mukhopadhyay, S., et al. (2023). A comprehensive review on the impacts of smoking on the health. PMC. Retrieved from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10625450/ PMC

- Goldade, K., Okuyemi, K. S., & Ahluwalia, J. S. (2012). Applying anthropology to eliminate tobacco-related health disparities: Opportunities and future directions. Global Public Health, 7(3), 281-295. PMC. Retrieved from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3430467/ PMC

- American Lung Association. (n.d.). Health Effects of Smoking. Retrieved from https://www.lung.org/quit-smoking/smoking-facts/health-effects/smoking American Lung Association

- Giovino, G. A., et al. (2017). Tobacco smoking: Health impact, prevalence, correlates and interventions. PMC. Retrieved from https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5490618/ PMC

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2004). The Health Consequences of Smoking. NCBI Bookshelf. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK44695/ NCBI

- Sobranowicz, P. (2011). Tobacco. Annual Review of Anthropology, 40, 25-49. Retrieved from https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev-anthro-091908-164527 Annual Reviews

- Bell, K. (2013). Towards a critical anthropology of smoking: Exploring the public health grip. Health Education Research, 22(3), 282-289. Retrieved from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/009145091304000102 SAGE Journals

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2024). Cigarette Smoking & Tobacco Use. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/about/index.html CDC

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2023). Tobacco: Key facts and global health impacts. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco