AI Answer Evaluation Platform Live Now. Try Free Answer Evaluation Now

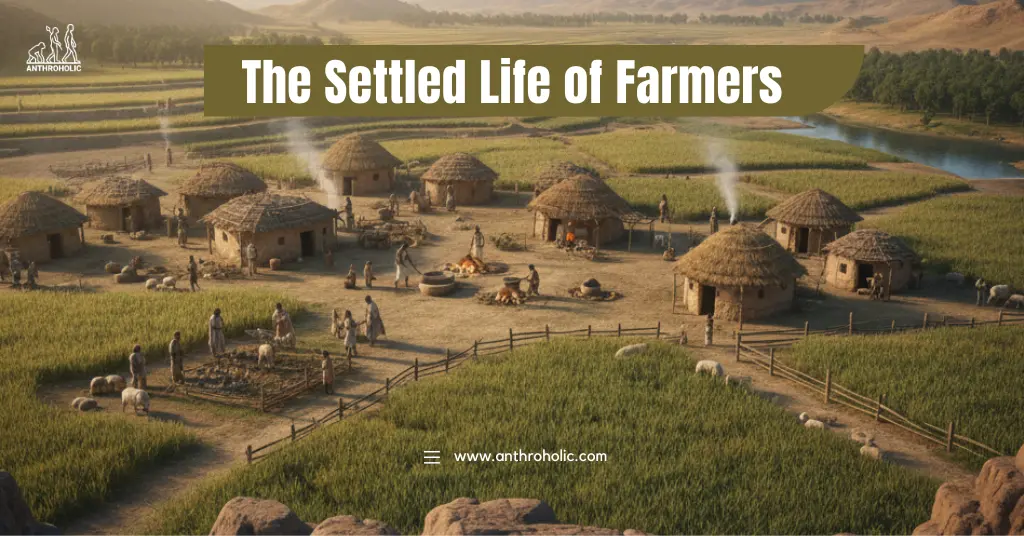

The Settled Life of Farmers

Imagine a small hillside village at dawn ploughs drawn, cattle grazing, fields tilled and ready for sowing. This scene captures what we mean by the settled life of farmers: communities rooted in one place, working the land year after year. In anthropological terms, the transition to settled agrarian livelihoods is one of the most profound shifts in human history it transformed social structure, economy, culture and landscape.Imagine a moment in human history when the constant pursuit of food ceased to dominate every waking hour.

No longer endlessly following herds or searching for seasonal fruit, humans planted a seed and chose to wait. This seemingly simple act the shift from a nomadic hunter-gatherer existence to the settled life of farmers was, in the eyes of anthropology, the single most profound transformation in the human journey.

Known as the Neolithic Revolution (or First Agricultural Revolution), this transition, beginning around 12,000 years ago, was not a sudden “flash of genius” but a gradual, complex process of domestication and sedentism. Its significance cannot be overstated: it laid the foundational blueprint for our modern world, enabling everything from villages and social stratification to states and global economies

What Does “Settled Life of Farmers” Mean?

In anthropological and agrarian studies, the term settled farming (or sedentary agriculture) refers to a mode of cultivation where agricultural communities live permanently on the same land and farm it over multiple seasons. This is in contrast to mobile or shifting-cultivation systems. According to one definition, sedentary farming “refers to farming that takes place in a single land by a settled farmer without rotating or shifting the fields.”

Anthropologists describe the settled life of farmers as more than farmland use: it is a lifestyle characterised by fixed dwellings, year-round occupation, accumulation of property and complex social organisation. For example, in the entry on farming, the author notes:

“Agriculture has also had a major environmental impact… Humans, plants and animals developed co-dependence.”

The Roots of Revolution: Domestication and Sedentism

The settled life of farmers rests on two interconnected pillars: domestication and sedentism. While often linked, archaeological evidence suggests they did not always occur simultaneously or in the same order across different regions of the world.

The Dawn of Domestication

Domestication is the process by which humans gain genetic control over the reproductive cycles of plants and animals, making them more useful for human consumption. This led to recognizable changes, known as the “domestication syndrome,” in species like wheat, barley, goats, and sheep.

- Plant Traits: Selected for traits like non-shattering heads (seeds staying attached to the stalk for easier harvesting), increased seed size, and simultaneous ripening.

- Case Study: The wild ancestor of maize, teosinte, looks vastly different from modern corn, illustrating millennia of intentional human selection.

- Animal Traits: Selected for traits like reduced aggression, smaller horns/antlers, and faster growth for meat, or increased yield for milk and wool.

The earliest centers of domestication, such as the Fertile Crescent (Southwest Asia) around 10,000–8,000 BCE, provided the “founder crops” (wheat, barley, lentils) and animals (goats, sheep, pigs) that fueled the initial spread of agriculture. Other independent centers followed in China (rice, millet), Mesoamerica (maize, beans, squash), and the Andes (potato, llama).

The Choice of Sedentism

Sedentism is the practice of living in permanent, year-round settlements. While farming often necessitates a settled life to tend and harvest fields, some earlier, non-agricultural groups—like the Natufian culture in the Levant began building semi-permanent villages due to rich, localized wild resources.

The shift to sedentism created a positive feedback loop:

- Fixed Homes: Allowed for the accumulation of non-portable material goods, such as pottery (for cooking and storage) and heavy grinding stones.

- Increased Fertility: Sedentary women often had higher fertility rates than nomadic foragers, partly because they stopped lactational amenorrhea (infertility while breastfeeding) sooner, as they didn’t need to constantly carry infants during long treks. This led to exponential population growth.

- Pressure to Produce: The resulting larger, denser populations placed greater pressure on wild resources, ultimately pushing groups toward a greater commitment to intensive agriculture to sustain themselves.

Social Reorganization: The Birth of Complexity

The settled life fundamentally restructured human society, moving beyond the small, relatively egalitarian bands of hunter-gatherers. Anthropologists use terms like chiefdoms and early states to describe the complex societies that eventually emerged from farming villages.

Key Features of the Settled Farming Life

Characteristics

In settled farming communities, certain features tend to recur:

- Permanent residence: The farmer and family live on or near the land they cultivate year-after-year.

- Fixed land tenure: Rights or claims to a plot of land become stable over long term.

- Crop cultivation (and often livestock) rather than purely hunting/gathering or shifting.

- Investment in infrastructure: Irrigation, storage, dwellings, fences, tools.

- Idle periods replaced with scheduled cultivation: fallow periods shorten as fields are reused more intensely.

- Generation of surplus (in many cases): enabling trade, accumulation, or non-farm activities.

- Strong family/kin ties and often labour passed across generations tied to a specific patch of land.

Advantages and Disadvantages

Advantages of settled farming life:

- Stability of food supply through cultivation year after year.

- Possibility of surplus generation, storage and trade.

- A fixed home fosters social institutions, education, community organisation.

- Land improvements and infrastructure can raise productivity.

Disadvantages/Challenges:

- Soil exhaustion, erosion, or decline in fertility if fallow periods shorten.

- Labour demands increase, especially for irrigation and maintenance.

- Fixation on land can reduce flexibility to adapt to ecological changes.

- Inequalities can emerge: those who control best land or resources may dominate peers.

Transition from Mobility to Sedentism

The shift to a settled farming life is not simply a technical change but also a deep cultural transformation. The Neolithic period witnessed the move from hunter-gatherer mobility to village-based settlement. One source remarks:

“Before the agricultural revolution (10,000–12,000 years ago), hunting and gathering was, universally, our species’ way of life.”

In South Asia, for example, research on the Adi tribe in Arunachal Pradesh shows how the shift from shifting cultivation to settled cultivation gradually took place. In these cases:

- Settlement required investment in stone walls or terraces.

- Households with better economic status were more likely to adopt settled cultivation.

- Cultural rituals linked to traditional cultivation cycles sometimes impeded full transition to sedentism.

Real-World Case Studies

Arial View: India’s Hill Farmers

In the study of the Adi tribe in Arunachal Pradesh, researchers found that although government programmes promoted settled cultivation, approximately 90 % of families still practiced shifting cultivation in 2016. The reasons included: terrain unsuitability, cultural preferences, labour‐intensity of fixed plots, and requirement of investment. This illustrates how even when settled cultivation is available, social and ecological factors shape farmer choices.

Global History: From Foragers to Settled Farmers

Anthropologist J. Carey (2023) argues that the transition to settled farming happened in multiple regions independently and was driven by local ecological opportunity and social change.The sustained settlement enabled population growth, development of craft, storage, and more complex political structures.

Data Insight – Demographic Impacts

Studies show that settled agricultural populations tend to expand both numerically and territorially. For example, courses in agrarian anthropology note that populations under settled agriculture show higher densities and larger home villages than mobile groups.

Cultural and Societal Implications

Social Stratification, Land Ownership and Identity

The settled life of farmers gives rise to new social dynamics. As land becomes fixed property, ownership, inheritance, and inequality take on new forms. Early scholars of agrarian societies noted how land-owning farmers developed distinct status from landless labourers. The settled life thus intersects with class, caste, ethnicity and gender.

Rituals, Seasons and Farm Life

Sedentary farming communities develop cultural calendars tied to sowing, harvest, and other agricultural milestones. These rituals reinforce the identity of farming families and tie them to the land. For instance, in the Adi case, festivals associated with swidden cultivation persisted even as some farms moved to settled cultivation.

Environmental Adaptation and Resilience

While settled farming may increase productivity, it also places long-term strain on soils, water systems and ecological cycles. Farmers must adapt through rotations, fallow management, and technologies such as irrigation. The anthropological lens emphasises that the farmer’s relationship to land is simultaneously ecological, cultural and economic.

Conclusion

The settled life of farmers represents one of the deepest transformations in human social history—a shift from mobile subsistence to rooted agrarian existence. This transition not only altered how people made a living but also reshaped social institutions, culture, landscape and identity. Through permanent residence, land investment, and social organisation around farming, sedentary farmer communities built the frameworks for villages, craft, markets and states.

Yet the settled life brings its own challenges: ecological risks, labour demands, property inequalities and adaptation pressures. Anthropology teaches us that understanding these farmers’ lives requires more than economic metrics it requires exploring the interplay of culture, ecology and material practice.

As we consider the 21st-century challenges of climate change, land rights and food security, the settled life of farmers remains deeply relevant. It underscores how human survival, culture and economy converge around the land. Farming may root us in place but it also carries the seeds of our future.

“Agriculture has always engaged with agrarian people… Even the most technologically-advanced farming systems are situated in environments of soil, water, and social relationships.”

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the difference between shifting cultivation and the settled life of farmers?

Shifting cultivation involves moving plots and letting previous fields lie fallow; the settled life of farmers involves staying in one place and cultivating the same land over multiple seasons.

Q2: Why did humans adopt settled farming in the first place?

Multiple factors: ecological changes, declining wild resources, population pressure, and social incentives for surplus storage and settlement.

Q3: Are all farmers “settled” today?

No. Many small-scale farmers still experience semi-mobile practices, fallow rotation, or land tenure insecurity. The transitional forms persist in many regions.

Q4: What are the key challenges of the settled farmer’s life?

Soil fertility decline, water scarcity, labour intensification, market pressures, and social inequality.

Q5: How is the settled life of farmers relevant for anthropological study?

It illuminates how human livelihoods, culture, land use and economy intersect making it a core focus of agrarian anthropology, economic anthropology and rural sociology.

References

- Childe, V. G. (1936). Man Makes Himself. Watts & Co. https://archive.org/details/manmakeshimself0000chil

- Diamond, J. (1987). The Worst Mistake in the History of the Human Race. Discover Magazine. https://www.discovermagazine.com/planet-earth/the-worst-mistake-in-the-history-of-the-human-race

- Graeber, D., & Wengrow, D. (2021). The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. https://us.macmillan.com/books/9780374157357/thedawnofeverything

- Larsen, C. S. (2023). The Bioarchaeology of the Neolithic: Health, Diet, and Lifestyle. Cambridge University Press. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/bioarchaeology

- Scott, J. C. (2017). Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States. Yale University Press. https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300182910/against-grain

- Smith, B. D. (2025). The Emergence of Agriculture: New Insights from Ancient DNA. Journal of Anthropological Research, 81(1). https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/toc/jar/current