AI Answer Evaluation Platform Live Now. Try Free Answer Evaluation Now

Forensic Facial Reconstruction

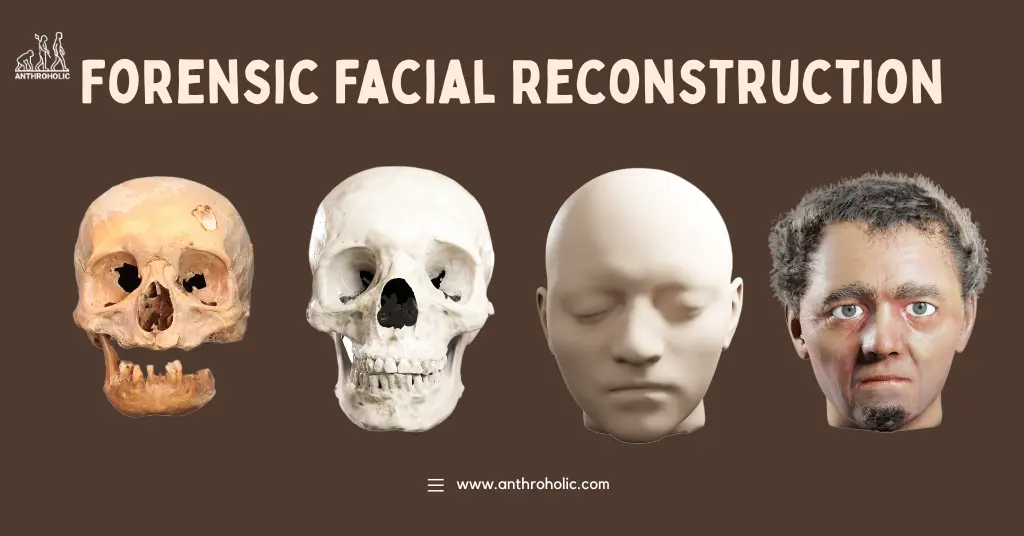

Imagine holding a skull a silent, anonymous relic of a life lost. Within those bone structures lies the potential to resurrect a face, to give a name back to the unknown dead. This is the profound mission of Forensic Facial Reconstruction (FFR), a multidisciplinary field that straddles the line between meticulous science and evocative art.

In forensic anthropology, positive identification achieved through fingerprints, dental records, or DNA is the gold standard. However, when decomposition or destruction renders these methods impossible, FFR becomes the vital last resort. It transforms a cold, anonymous object into a recognizable human face, often providing the crucial lead that stimulates public memory and leads to identification. For students and enthusiasts of anthropology, understanding FFR is key to grasping the discipline’s critical role in both modern forensics and the reconstruction of ancient human history.

The Anthropological Cornerstone of Identity

Forensic Facial Reconstruction is the process of recreating the likeness of an individual from their skeletal remains through an amalgamation of anthropology, osteology, anatomy, and artistry. The underlying principle is the consistent biological relationship between the skull’s bony contours and the overlying soft tissues of the face.

Significance in Anthropology

While most commonly associated with criminal investigations, FFR has deep roots in Biological Anthropology and Archaeology. Early anthropologists used facial approximation to bring ancient hominids and historical figures to life, moving beyond dry osteological reports to offer a tangible image of our evolutionary past. Figures like Mikhail Gerasimov, a pioneer in the field, applied his techniques not just to forensics but also to reconstruct the faces of historical figures like Ivan the Terrible. This application solidifies FFR’s position as a powerful tool for visualising and communicating anthropological data.

“The face is the billboard of the human body, the most distinctive feature an individual possesses, and the one most likely to be recalled by family, friends, and witnesses.” A prominent theme in forensic identification literature.

Methodologies of Forensic Facial Reconstruction

Facial reconstruction techniques are broadly categorised by their dimensionality and the tools used, evolving significantly from manual sculpting to advanced computing.

I. Three-Dimensional (3D) Reconstruction

The 3D approach involves building a physical or virtual representation directly onto a replica of the skull. These methods rely heavily on facial tissue depth data, which provides average measurements of tissue thickness (skin, fat, muscle) at specific anatomical landmarks across the face, stratified by age, sex, and ancestry.

A. Manual 3D Methods (Sculpting)

Manual methods are the classic form of FFR, combining the forensic anthropologist’s anatomical expertise with the forensic artist’s sculpting skill. They are primarily divided into three schools of thought:

| Method | Key Features | Developers/Pioneers |

| Anatomical (Russian) Method | Models facial muscles layer-by-layer before adding skin. Less reliance on average tissue depth data; focuses on muscle anatomy. | Mikhail Gerasimov |

| Anthropometrical (American) Method | Relies on pre-determined tissue depth markers (pegs or dowels) placed on the skull. Soft tissues are then added in bulk to meet the marker heights. | Wilton M. Krogman, Betty Pat Gatliff, Clyde Snow |

| Combination (Manchester) Method | The most accepted modern manual technique. It combines the muscle modelling of the Russian method with the tissue depth markers of the American method for a more refined result. | Richard Neave |

The process typically begins with a detailed skull assessment to determine the biological profile (sex, age, ancestry). A cast of the skull is prepared, prosthetic eyes are inserted into the orbits, and the nose, lips, and ears features with limited bony structure are approximated using guidelines and anatomical averages. Finally, the soft tissues are sculpted, using the depth markers as guides until the clay covers them completely.

B. Computerised 3D Methods

With the advancement of technology, computer-aided FFR is now widely used.

- Process: The skull is scanned using a Computed Tomography (CT) scan or laser scanner to create a 3D digital model (often an STL file). This digital skull is imported into specialised graphics software (e.g., FreeForm, Geomagic, Blender).

- Technique: Digital tissue depth markers are placed, and the virtual soft tissue is modelled. Some systems use large databases of 3D facial scans to morph a face onto the skull, automating parts of the process.

This method offers several advantages: it is non-destructive to the remains, it’s faster, and modifications (like adding different hairstyles or weight variations) can be made quickly and cost-effectively, which is essential for investigative updates.

II. Two-Dimensional (2D) Reconstruction

2D reconstruction is the least invasive and involves creating a drawing or digital image.

- Manual Sketching: A forensic artist draws the face based on the skull’s shape and the application of tissue depth data onto frontal and lateral photographs of the skull.

- Computerised Compositing: Software is used to composite a face using stock photographic features (eyes, noses, mouths) that are scaled and manipulated to fit the underlying skull image.

While less lifelike than 3D models, 2D sketches can be rapidly disseminated for public appeals.

The Controversy of Accuracy and Subjectivity

Despite its successes, FFR remains a controversial technique in the judicial and academic communities.

Accuracy and Reliability

FFR produces a facial approximation or likeness, not an exact portrait. The final face is heavily influenced by factors that cannot be definitively determined from the skull:

- Tissue Depth Averages: While comprehensive, these are averages. An individual’s actual tissue thickness can vary widely based on weight changes, diet, and genetics. A 2025 study on computerized FFR demonstrated that a significant percentage of reconstructed facial surfaces had an error of less than $2.5\text{ mm}$ when compared to the target face, suggesting an acceptable level of prediction for recognition, yet not a perfect match (Lee et al., 2025).

- Missing Features: The nose, ears, eyelids, and lips are largely composed of cartilage and soft tissue, leaving their final form to the skill and interpretation of the artist based on general anthropological guidelines.

- Individuating Characteristics: Hair, wrinkles, and specific muscle tone are often unknown and must be approximated, creating a “best-guess” scenario.

Due to this inherent subjectivity, FFR is typically considered a tool for circumstantial identification it generates a lead rather than a method for positive identification in a court of law.

“A reconstruction can only reveal the type of face a person may have exhibited. It provides a means of recognition, not a proof of identity.”

Case Study: The Face of Richard III

A powerful example of FFR’s dual use is the 2013 identification of King Richard III. After his skeletal remains were exhumed, the Combination (Manchester) method was used to reconstruct his face. The resulting image generated intense public interest and, combined with DNA analysis, provided a definitive likeness of the last Plantagenet king, illustrating FFR’s enduring cultural and historical value beyond forensics (Wilkinson et al., 2014).

Conclusion

Forensic Facial Reconstruction is an indispensable bridge between the past and the present, the unknown and the identified. It synthesizes the foundational principles of anatomy, osteology, and artistic interpretation, providing a mechanism to visually restore the humanity of those who would otherwise remain nameless. As technological advancements continue to refine tissue depth data collection (such as with Cone-Beam CT scanning) and automate parts of the reconstruction process, the accuracy and utility of FFR will only increase. For those studying anthropology, FFR offers a tangible, impactful example of how the meticulous study of human remains directly serves societal needs be it resolving a cold case or giving a face to a long-lost ancestor.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Is Forensic Facial Reconstruction admissible as evidence in court?

A: Generally, no. FFR is a highly valuable investigative tool used to generate leads for public recognition. Because the final result is an approximation that contains a degree of artistic subjectivity and relies on statistical averages (facial tissue depth), it does not meet the legal standard for positive identification (which requires methods like DNA, dental records, or fingerprints).

Q2: What part of the face is the most difficult to reconstruct?

A: The nose is widely considered the most difficult feature. While the nasal aperture (the bony opening) gives a basis for its width and projection, the bulk of the nose is composed of cartilage, which does not survive decomposition. Its final shape, including the tip and alar wings, must be estimated using anthropological guidelines related to the nasal aperture’s width and shape.

Q3: How do forensic specialists determine a reconstructed face’s hair and eye colour?

A: Since hair, eye colour, and skin tone are not preserved or dictated by the skull, they must be approximated based on the biological profile determined from the skeletal remains. Ancestry estimation, for example, can suggest a likely range of hair and eye colours. In forensic cases, artists will often create a set of slightly varied images with different hairstyles or features to maximise the chance of public recognition.

Q4: Besides crime solving, where else is FFR used?

A: FFR is extensively used in paleoanthropology and archaeology to reconstruct the faces of ancient hominids (like Australopithecus or Neanderthals) and historically significant individuals (e.g., Egyptian mummies, medieval royalty). This application helps scientists and the public visualise the appearance of people from the distant past.

References

- An Overview of Forensic Facial Reconstruction. (2022). Hilaris Publisher. https://www.hilarispublisher.com/open-access/an-overview-of-forensic-facial-reconstruction.pdf

- Claes, P., Vandermeulen, D., & De Greef, S. (2006). Craniofacial reconstruction using a combined statistical model of face shape and soft tissue depths … Forensic Science International, 159(S147-S158). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2005.07.016

- Lee, W.-J., Wilkinson, C., & Hwang, H.-S. (2012). An accuracy assessment of forensic computerized facial reconstruction employing cone-beam computed tomography from live subjects. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 57(2), 318-327. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1556-4029.2011.01971.x

- Snow, C. C. (1979). Reconstruction of facial features from the skull: An evaluation of its usefulness in forensic anthropology. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 24(2), 305-316. https://doi.org/10.1520/JFS10983J

- Forensic Facial Reconstruction: The Final Frontier. (2014). Frontiers in Medical Anthropology, 9(2), 83-94. PMC. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4606364/