AI Answer Evaluation Platform Live Now. Try Free Answer Evaluation Now

How do people adapt to environmental extremes and other circumstances?

From the scorching sands of the Sahara to the frigid ice sheets of the Arctic, humanity has demonstrated an astonishing capacity for persistence and prosperity. Human beings are remarkable not simply because we survive in such places but because we adapt and thrive. The question of how people adapt to environmental extremes and other circumstances sits at the heart of anthropological inquiry into human resilience. How do people adapt to environmental extremes and other circumstances? This question lies at the very heart of Anthropology, serving as the foundational inquiry for understanding human biological and cultural diversity.

Anthropological study of adaptation, specifically within the subfields of Biological Anthropology and Cultural Anthropology, explores the interconnected biological, social, and technological adjustments humans make to cope with stress be it thermal, nutritional, hypoxic, infectious, or social.

The Anthropological Framework of Human Adaptation

Adaptation, in the anthropological context, is a process where human organisms or populations achieve a beneficial adjustment to their environment. It is a multi-faceted process that can be categorized into three primary, interacting levels: Genetic, Physiological (Acclimatization), and Cultural.

Genetic Adaptation (Evolutionary Change)

Genetic adaptation refers to changes in the frequency of specific genes within a population over many generations, conferring a reproductive or survival advantage in a particular environment. These are permanent, inherited biological traits.

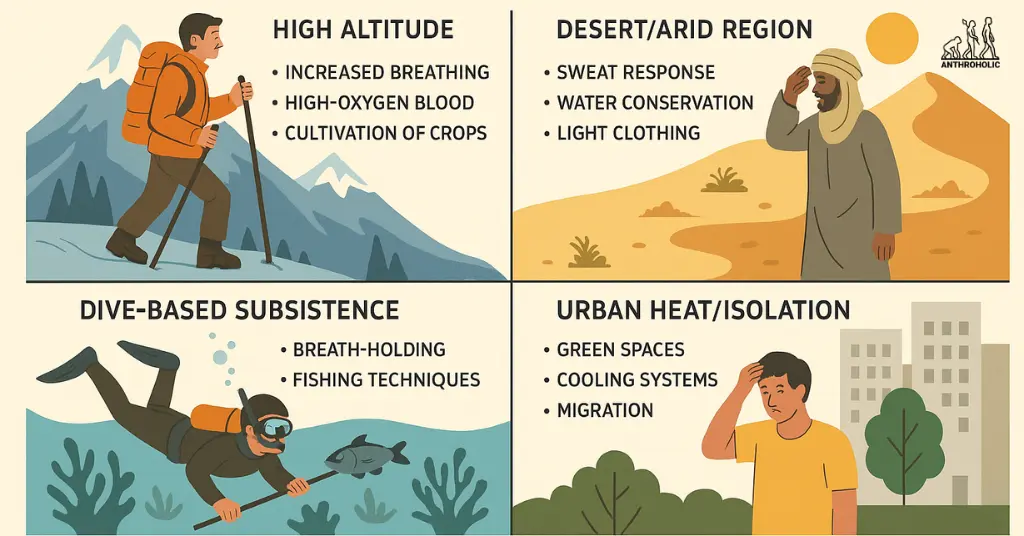

- High Altitude Adaptation: One of the most compelling examples is the difference between human groups living at high altitudes.

- Tibetans show a genetic trait (related to the EP AS1 gene) that allows them to process oxygen more efficiently. They have normal hemoglobin levels but breathe faster and have increased blood flow, preventing the risks associated with polycythemia (abnormally high red blood cell count).

- Andeans (like the Quechua) typically exhibit enlarged lung capacity and higher levels of hemoglobin, enabling more oxygen to be carried in the blood.

- Skin Color: The variation in human skin pigmentation is a clear genetic adaptation to the intensity of UV radiation. Darker skin near the equator protects against UV damage, while lighter skin at higher latitudes facilitates Vitamin D synthesis.

Physiological Adaptation (Acclimatization)

Physiological adaptation, also known as acclimatization or acclimation, refers to non-inherited, reversible changes that occur within an individual’s lifetime as a response to environmental stress. These adjustments are short-term or developmental.

| Type of Acclimatization | Definition | Example Case Study |

| Developmental | Irreversible, occurs during growth and development (e.g., childhood). | Children raised at high altitudes develop a permanently greater lung volume. |

| Short-Term (Acclimation) | Rapid, temporary response to immediate stress. | The tanning of skin after exposure to sunlight; shivering in cold weather. |

| Long-Term | Reversible changes over weeks or months of sustained exposure. | Reduced heart rate and blood pressure observed in newcomers spending months at altitude. |

“Culture is the ultimate adaptive mechanism of the human species. Where biological evolution takes millennia, cultural adaptation can occur within a single generation, offering flexibility and speed essential for survival in diverse and rapidly changing settings.”

The Power of Cultural Adaptation and Innovation

While biological adaptations provide the physical foundation for survival, cultural adaptation is arguably the most critical and flexible mechanism humans employ. Culture encompassing technology, economy, social organization, and beliefs acts as a buffer between the human organism and environmental stress.

Technological Solutions to Environmental Extremes

Cultural tools and practices overcome limitations that would be impossible to breach through biology alone.

- Cold Environments (The Inuit Case Study): The traditional way of life among the Inuit (formerly Eskimo) of the Arctic exemplifies profound cultural adaptation to extreme cold.

- Shelter: Construction of the igloo (snow house) and qarmaq (turf house), which efficiently trap heat.

- Clothing: Development of layered, tailored clothing made from caribou and seal skin, creating highly effective insulation.

- Diet: A high-fat, high-protein diet (marine mammals and caribou) provides the necessary caloric energy for thermoregulation.

- Arid Environments (Water Scarcity): Groups like the Bedouins of the Arabian desert adapted through unique technologies and practices:

- Clothing: Wearing loose, flowing, dark clothing paradoxically aids in cooling by creating a bellows effect to circulate air and protecting the body from direct solar radiation.

- Mobility: Nomadic pastoralism allows them to follow sparse rainfall and avoid resource depletion in any single area.

Socio-Political and Economic Adaptation

Adaptation extends beyond purely ecological factors to address social and economic circumstances, such as poverty, political upheaval, and globalization.

- Migration and Diaspora: When environmental conditions (like climate change leading to droughts or sea-level rise) or social instability become unmanageable, human populations adapt by migration. This is a dramatic cultural strategy that allows groups to relocate to areas of greater resource security or political safety. This involves adapting social structures, kinship ties, and economic strategies to a new host country.

- The Informal Economy: In circumstances of poverty or structural inequality, many urban populations adapt by creating robust informal economies (e.g., street vending, recycling, undocumented services). According to a 2023 study on global labor, the informal sector is a critical adaptive mechanism, providing subsistence livelihoods for over 60% of the world’s employed population in developing regions. (Internal Link: Learn more about the Anthropology of Poverty and Economic Adaptations).

- Kinship Flexibility: Under conditions of resource scarcity or high male out-migration for labor, many societies demonstrate flexibility in kinship and household structure. For instance, the rise of matrilocal or female-headed households in some communities is an adaptive response to maintain social cohesion and economic viability.

The Role of Belief Systems

Belief systems, myths, and rituals can also function as adaptive mechanisms by regulating resource use and providing psychological comfort.

- Ecological Rationality of Taboos: Anthropologist Marvin Harris argued that seemingly irrational food taboos (like the prohibition against eating beef in India) have an ecological rationality the cattle are more valuable alive (for traction and milk) than slaughtered, especially in resource-scarce environments. This cultural rule serves to protect a vital resource.

- Psychological Resilience: Rituals and shared cosmological beliefs offer populations a way to cope with unpredictable natural disasters, famine, and death, reinforcing social solidarity and psychological resilience necessary for group survival.

Conclusion: The Adaptive Mosaic

Human adaptation is not a simple, linear process but a dynamic, interwoven mosaic of genetic inheritance, physiological responses, and cultural ingenuity. Our unparalleled success as a species stems from the redundancy and flexibility built into this adaptive system. We have seen how populations from the Tibetan Plateau to the Kalahari Desert employ sophisticated, localized strategies from the molecular level of gene expression to the societal level of economic organization to not only survive but to define life in their respective environments.

The study of adaptation remains critically important. As the world faces new extremes accelerated climate change, global pandemics, and unprecedented social inequality understanding the mechanisms that have allowed human groups to persist for millennia offers vital lessons for creating resilient, sustainable futures.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the main difference between acclimatization and genetic adaptation?

A: Genetic adaptation is an inherited, permanent change in a population’s genetic makeup that occurs over many generations (evolutionary time). Acclimatization is a non-inherited, reversible physiological change that happens within an individual’s lifetime (e.g., increased red blood cell count at high altitude) to cope with immediate environmental stress.

Q2: How does climate change impact human adaptive strategies?

A: Climate change is creating rapid and novel environmental pressures (extreme heat, unpredictable rainfall, sea-level rise). This forces human groups to rely more heavily on rapid cultural adaptations such as mass migration, shifts in agricultural practices (e.g., switching to drought-resistant crops), and the development of new technologies (e.g., water harvesting). It often pushes biological and cultural limits simultaneously.

Q3: What is “stress” in the context of anthropological adaptation?

A: Anthropologically, stress refers to any force or condition (environmental, social, or biological) that potentially threatens the maintenance of health, equilibrium, or survival. Examples include thermal stress (extreme heat/cold), hypoxic stress (lack of oxygen at high altitude), nutritional stress (famine), or socio-economic stress (poverty or conflict).

Q4: Can cultural adaptations ever be maladaptive?

A: Yes. A maladaptive trait is one that decreases an organism’s or population’s ability to survive and reproduce in a specific environment. For example, relying on highly centralized, water-intensive monoculture agriculture might be a short-term economic adaptation but becomes maladaptive in the face of long-term climate-induced drought.

References

- “Human adaptation to extreme environmental conditions” (PMC) – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7193766/ PMC

- “Human Bodies in Extreme Environments” (Annual Reviews in Anthropology) – https://www.annualreviews.org/content/journals/10.1146/annurev-anthro-052721-085858 Annual Reviews

- “Human Adaptation to Extreme Environments: A Biocultural Perspective” – https://www.walshmedicalmedia.com/open-access/human-adaptation-to-extreme-environments-a-biocultural-perspective-134585.html @WalshMedical

- “A Review of Anthropological Adaptations of Humans Living in Extreme …” (Human Biology) – https://www.bioone.org/journals/human-biology/volume-94/issue-3/hub.2017.a925563/A-Review-of-Anthropological-Adaptations-of-Humans-Living-in-Extreme/10.1353/hub.2017.a925563.full BioOne

- “Adaptation to Extreme Environments in an Admixed Human …” (Genome Biology and Evolution) – https://academic.oup.com/gbe/article/11/9/2468/5544110 OUP Academic

- “Human adaptation to extreme environmental conditions” (Elsevier/ScienceDirect) – https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0959437X18300777 ScienceDirect

- “Human challenges to adaptation to extreme professional …” (PubMed) – https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36682426/ PubMed

- “Editorial: Survival in Extreme Environments – Adaptation and Evolution?” (Frontiers in Physiology) – https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/physiology/articles/10.3389/fphys.2022.836210/full Frontiers

- “Evolutionary mismatch and the role of G × E interactions in human disease” (arXiv pre-print) – https://arxiv.org/abs/2301.05255