AI Answer Evaluation Platform Live Now. Try Free Answer Evaluation Now

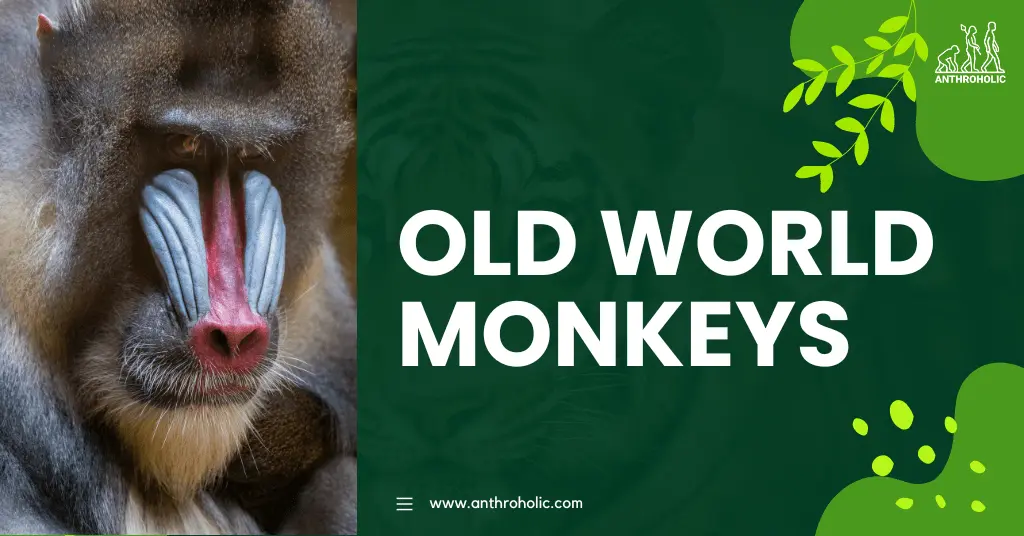

Old World Monkeys

Old World monkeys, scientifically known as Cercopithecidae, are a large and diverse family of primates that hail from Africa, Asia, and Europe. They are referred to as “Old World” monkeys because they are native to the parts of the world that are known historically as the “Old World.” With about 138 species encompassing 23 genera, Old World monkeys represent one of the two subfamilies under the catarrhine or “downward-nosed” group of primates, the other being the apes and humans (Napier & Napier, 1967).

Physical Characteristics

While diverse in many respects, Old World monkeys share a few distinguishing physical characteristics:

- Nasal Structure: Old World monkeys have nostrils that are close together and point downwards.

- Tail Structure: Unlike New World monkeys, many Old World monkeys don’t have prehensile tails, meaning they cannot use their tails to grab onto things.

- Dental Structure: Old World monkeys have dental formula of 2:1:2:3, i.e., two incisors, one canine, two premolars, and three molars (Fleagle, 1999).

- Cheek Pouches: Many species have cheek pouches, which allow them to gather food quickly and then chew it later.

The diversity in size and weight among Old World monkeys is astounding, ranging from the 1-kilogram talapoin monkey to the male mandrill, which can weigh up to 50 kilograms.

| Species | Minimum Weight (kg) | Maximum Weight (kg) |

|---|---|---|

| Talapoin | 0.8 | 1.3 |

| Mandrill | 10 | 50 |

Classification and Distribution

Old World monkeys are further divided into two subfamilies: Colobinae, or leaf-eating monkeys, and Cercopithecinae, or cheek-pouched monkeys. The distribution of these monkeys spans various parts of the globe, from rainforests to savannahs and mountainous regions.

Colobinae includes monkeys such as colobus, langurs, and proboscis monkeys, known for their complex stomachs that allow them to digest a largely herbivorous diet.

Cercopithecinae is more diverse and includes baboons, macaques, vervets, and guenons. These monkeys tend to have a more omnivorous diet and are known for their cheek pouches, which they use to store food.

Behavioral and Social Structures

Old World monkeys exhibit a wide range of social behaviors. Many, like baboons and macaques, are known for their highly structured social hierarchies. For instance, in baboon troops, both males and females have a dominance rank (Cheney & Seyfarth, 2007).

Most Old World monkeys are diurnal (active during the day) and live in a variety of terrestrial and arboreal environments. Some species, such as baboons and macaques, have even adapted to human-modified environments and are often found in urban areas (Thompson, 2019).

Conservation Status

Several species of Old World monkeys are currently under threat due to habitat loss, hunting, and climate change. Some, like the Proboscis monkey and the Roloway monkey, are listed as endangered or critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Preservation of these species and their habitats is crucial for maintaining biodiversity.

The Primate Diaspora

Old World monkeys represent an important juncture in primate evolution. They’ve migrated and diversified across the globe, adapting to varied climates and ecological niches. Their adaptive versatility provides valuable insight into the myriad evolutionary pathways available to primates.

The Fruits of Omnivory

Old World monkeys are predominantly omnivores, consuming a wide range of plant and animal material. The highly adaptable macaques, for instance, are known to have diets that include fruits, leaves, insects, and even small mammals (Marshall & Wrangham, 2007). This dietary flexibility has allowed them to exploit a wide range of habitats, further enriching their evolutionary tapestry.

Reproduction and Development

In terms of reproduction, Old World monkeys typically have a single offspring at a time, which results in intensive parental care. The gestation period varies between species, ranging from five to seven months.

From a developmental perspective, most Old World monkeys have long periods of immaturity and adolescence. This prolonged period of youth allows for extensive learning and socialization, which are essential for survival in their complex social structures (van Schaik, 2016).

The Old World Monkeys and Humans

Old World monkeys and humans have had a long-standing relationship, which ranges from cultural and religious reverence to conflict. The reverence is exemplified by the rhesus macaques of India, considered sacred in Hindu culture. Conversely, human-monkey conflict is evident in urban areas, where monkeys often raid crops and become pests.

Future Research Directions

The study of Old World monkeys continues to unfold new dimensions in understanding primate evolution, ecology, and behavior. Furthermore, their evolutionary success and widespread distribution point towards an adaptive flexibility that may provide insights for human adaptation in the face of climate change and habitat loss.

As research continues, it is hoped that increasing understanding of these complex creatures will aid conservation efforts and inform broader biological and anthropological discussions. The potential they offer for unlocking mysteries about our own species and the world we share makes the Old World monkeys an exciting area of study in primatology.

Conclusion

The Old World monkeys, as part of our evolutionary family, hold significant value in understanding our own species’ history and behavioral adaptations. Their diverse ecological roles and behavioral complexities continue to contribute to the intriguing and vital field of primatology in anthropology.

References

[1] Cheney, D., & Seyfarth, R. (2007). Baboon Metaphysics: The Evolution of a Social Mind. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/226441792_D_L_Cheney_R_M_Seyfarth_Baboon_Metaphysics_The_Evolution_of_a_Social_Mind_A_Review

[2] Fleagle, J. G. (1999). Primate Adaptation and Evolution. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

[3] Napier, J. R., & Napier, P. H. (1967). A Handbook of Living Primates. London, UK: Academic Press.

[4] Thompson, M. E. (2019). Primate Behavioral Ecology. London, UK: Routledge.

[5] Marshall, A. J., & Wrangham, R. W. (2007). Evolutionary consequences of fallback foods. International Journal of Primatology, 28(6), 1219–1235. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10764-007-9218-5

[6] van Schaik, C. P. (2016). The Primate Origins of Human Nature (Vol. 3). Wiley-Blackwell.