AI Answer Evaluation Platform Live Now. Try Free Answer Evaluation Now

Anthropology

The name “anthropology” originates from the Greek words “anthropos,” which means “human,” and “logos,” which means “study,” “science,” or “knowledge.” Together, they create the word “anthropologos,” which refers to the study of humans. The phrase was first given to a new academic discipline that aimed to explain the diversity of human societies and civilizations at the beginning of the 19th century. The word “anthropology” was first used in the English language by British philosopher and scientist William Whewell in the 1820s. He used phrase to designate the study of human nature and society, which comprises the analysis of language and social structure, physical and cultural features, and the process of human evolution and development. The word “anthropology” was ultimately employed to represent the study of human physical attributes and, separately, the evolution and development of people by anthropologists like the German anthropologist Ernst Haeckel and the French anthropologist Paul Broca. In the second half of the 19th century, the term “anthropology” was used to refer to the study of human civilizations and cultures, including their social structure, habits, beliefs, and linguistic patterns.

Evolution and History of Anthropology

Anthropology in the 19th Century

The academic subject of anthropology emerged in the 19th century. The 19th century saw the following notable breakthroughs and trends in anthropology:

- Ethnography: The 18th century, when European explorers first began travelling overseas and making contact with foreign civilizations, might be regarded as the birth year of anthropology. These connections stimulated curiosity in the diversity of human groups and cultures, which led to the development of the field of ethnography, which explores cultures and civilizations via attentive observation and interaction.

- Anthropologists like Lewis Henry Morgan and Franz Boas are credited with developing the idea of cultural evolution. It asserts that societies and cultures grow and advance over time. This idea had a significant influence on the development of the anthropology field known as “cultural anthropology“.

- Comparative technique: To better comprehend the similarities and differences between diverse cultures and societies, anthropologists have started to employ the comparative technique, which entails contrasting and comparing.

- To analyze human groups and civilizations, many anthropologists in the 19th century adopted Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution [1]. This hypothesis describes the evolution of human communities and civilizations.

- Colonialism and imperialism: During the 19th century, anthropologists actively supported and legitimized the activities of colonial powers through their work. Because of this, the history of colonialism and imperialism in anthropology has sparked controversy and criticism.

- Classification and typology: In the 19th century, anthropologists made an effort to categorize various civilizations and tribes according to how sophisticated they were. The ethnological categorization method was later criticized for being extremely simplistic and having a tendency to caricature and reduce many civilizations to their most basic elements.

- Physical anthropology: The field has emerged as a distinct discipline in the 19th century and focuses on the study of human biology, evolution, and variation.

Anthropology in the 20th Century

In the 20th century, there were important developments and breakthroughs in the study of anthropology. Some important advancements and trends in anthropology throughout the 20th century are the ones highlighted below:

- Boasian Anthropology: Franz Boas, recognized as the “father of American anthropology,” educated a group of anthropologists who later explored the indigenous peoples of North America and contributed to the expansion of the subject in the nation. The notion of cultural relativism, which claims that civilizations should be examined and judged on their own terms rather than in line with the criteria of another culture, was also created by Boas and his supporters.

- Cultural anthropology: At the start of the 20th century, a unique branch of anthropology known as cultural anthropology was developed, emphasizing the ethnographic and participant observation study of human culture and civilization. Margaret Mead and Ruth Benedict are two writers who have looked at how gender and sexuality work in diverse cultural situations.

- The structural-functionalist school of social anthropology was founded by British scientists like A.R. Radcliffe-Brown and Bronislaw Malinowski. This field of social anthropology predominantly examines societal structure and order. They exploited the theory of functionalism to explain how all components of society interact to ensure continuity and stability.

- Integration of other disciplines: Physical anthropology, linguistics, and archaeology were a few of the areas that anthropology started to more extensively integrate in the middle of the 20th century. As a result, such subfields as linguistic anthropology and archaeology evolved.

- Cultural materialism stresses the link between technical progress, economic structures, and cultural practices. It was popularized by American anthropologist Marvin Harris. He maintained that cultural practices and ideas are determined by the underlying material circumstances of human civilization.

- Criticism of Anthropology: In the second half of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st, anthropologists began to think about the moral implications of their work and how colonialism and imperialism affected their field of study. Research into the historical behavior of anthropologists and the field of anthropology itself led to the development of a critical approach to anthropology.

- Applied Anthropology: The study of applied anthropology developed in the 20th century as a way to apply anthropological ideas, approaches, and knowledge to urgent issues including development, human rights, and public health.

Anthropology in the 21st century

In anthropology, the 21st century has seen both the persistence of a number of key trends and advancements and the emergence of new issues and challenges. A handful of the key developments and trends in anthropology in the twenty-first century are as follows:

- Globalization: With the world becoming more connected, anthropology is faced with both new opportunities and challenges. Anthropologists look at how people are adjusting to these changes and how globalisation has affected culture and society as a whole.

- Digital anthropology is a brand-new academic field that focuses on how technology is changing culture and society. It was developed as a result of the speedy development of digital technology.

- Public anthropology: In the twenty-first century, anthropology has gained more prominence for its contribution to addressing societal issues and influencing public policy. To apply their expertise and approaches to real-world issues, anthropologists are working with non-academic partners and organizations more often.

- Criticism of anthropology has been ongoing in the twenty-first century, with a focus on the discipline’s moral implications and the legacy of colonialism and imperialism, as well as criticism of historical anthropologists’ work and the profession itself.

- Multispecies anthropology: In the twenty-first century, anthropologists have started to carefully explore the connections and interactions between people and other species, including those of animals, plants, and microorganisms. This field of study is known as “multispecies anthropology.”

- Decolonization: In the twenty-first century, there has been a resurgence of interest in the need to decolonize the discipline of anthropology. In order to do this, it is necessary to acknowledge and challenge the ways in which colonialism and imperialism have influenced the profession and to work towards building a more inclusive and equal environment. For instance, in the field of environmental anthropology, anthropologists are starting to look into the interactions and relationships between human civilizations and the environment.

- Related concerns: The interconnections and implications of many forms of marginalization and oppression, such as those based on race, gender, class, and sexual orientation, are now being studied by anthropologists.

History of Anthropology Timeline

A general history of some major developments and events in the long-standing and intricate field of anthropology is offered below. The 18th century The study of human communities and cultures began to take shape as an independent field of study with the works of thinkers like Montesquieu and Voltaire, who looked at human variety and the origins of civilizations.

| In 1871, the first anthropological chair was founded at the University of Oxford. |

| In 1881, the American Association for the Advancement of Science created a branch for anthropology. |

| The first anthropology department was created in 1884 at the University of California, Berkeley. |

| The intellectual underpinnings of cultural relativism are explained in Franz Boas’ “The Philosophy of Anthropology,” which was printed in 1899. |

| In 1906, the American Anthropological Association (AAA) was formed. |

| The first anthropology PhD was given to Alexander Goldenweiser by Columbia University in 1922. |

| 1940s–1950s: During the Cold War and WWII, anthropologists cooperated with governmental organizations and participated in policymaking. |

| 1960s–1970s: There are emerging concerns about the history of colonialism in anthropology as well as the underrepresentation of individuals of color in the study. |

| Decolonization and postcolonialism were prominent anthropological ideas in the 1970s and 1980s. |

| 1990s–2000: Themes pertaining to globalization and transnationalism become more popular in anthropology. |

| In the twenty-first century, anthropology is continually growing, with a greater emphasis on its power to alter public policy and address social concerns. |

Importance and Scope of Anthropology

Anthropology’s importance lies in its ability to shed light on who we are as humans, how we have come to be the way we are, and how we interact with the world around us. It helps us understand the complex interplay of cultural, biological, historical, and environmental factors that shape human societies, and the implications of human behavior on a global scale. Here are some aspects that underpin the importance and scope of anthropology:

- Understanding Human Diversity: One of the most critical contributions of anthropology is its focus on human diversity. It helps us appreciate the vast variety of human cultures and societies, the differences in how people live, what they believe, and how they organize their societies. This understanding fosters mutual respect and cooperation among people from diverse backgrounds.

- Insights into Human Evolution and Biology: Biological anthropology provides significant insights into human evolution, our genetic links with other species, and our unique adaptations. It helps us understand the evolutionary history of diseases, human diet, and the genetics of populations.

- Language and Communication: Linguistic anthropology helps us understand how language shapes our world, influences our thinking, and allows us to communicate and pass knowledge across generations.

- Cultural Heritage and Historical Context: Through archaeology, anthropology enables us to explore the past, providing a historical context to contemporary issues and helping us understand our cultural heritage.

- Problem-Solving in the Modern World: Anthropologists often work on solving real-world problems. For instance, medical anthropologists study health and healthcare systems across cultures, informing healthcare policies and practices. Environmental anthropologists help address ecological concerns, while corporate anthropologists may contribute to improving workplace culture or designing user-friendly technologies.

- Informing Policy and Advocacy: Anthropology’s broad, holistic perspective can help inform public policy and advocacy efforts. Anthropologists often work on issues related to human rights, social justice, public health, education, and environmental conservation.

The Four Main Fields of Anthropology

Cultural Anthropology: Understanding Culture and Society

- Cultural Anthropology is a major division of anthropology that centers on the study of cultural variation among humans and is fundamental to our understanding of human society.

- It involves examining the norms, values, ideas, behaviors, and artifacts of groups of people, with the aim of interpreting the complexities of their cultures.

- The concept of culture as employed in anthropology is broad, encompassing all aspects of human life including language, religion, social structures, art, and technology.

- Cultural anthropologists argue that culture shapes our perception of reality and guides our behavior, and as such, understanding culture provides insight into why people behave the way they do [2].

- Cultural anthropology also emphasizes cultural relativism, the idea that a person’s beliefs, values, and practices should be understood based on their own culture, rather than judged by the standards of another [3].

- This perspective allows anthropologists to appreciate the diversity of human cultures and counter ethnocentric views.

“Social anthropology” and “cultural anthropology” were considered separate disciplines in the 1920s. Radcliffe-Brown and Bronislaw Malinowski established the boundary between social and cultural anthropology in 1930. Social-cultural anthropology, i.e. the synthesis of sociology and anthropology was first explored by experts in the respective domains, Both these disciplines were interested in a common “science of society”. Scholarly specialization, disparities in study areas, geographic concentrations, and methodological considerations divided the two disciplines during the 20th century. Today, globalization has encouraged a partial reconvergence of methodologies and subjects during the previous few decades, but not of worldviews, ethos, or academic institutions. Before World War II, the disciplines of “social” and “cultural” anthropology were still distinct. During the war, Anthropologists played a significant role in European resettlements and provided advice on racial status issues in controlled territories. Following the war, anthropologists combined their theories and research methods to create the collective field known as “sociocultural anthropology.” Academic interests included those in community studies, kinship, acculturation, and religion.

Biological or Physical Anthropology

Biological anthropology, also known as physical anthropology, is a subfield of anthropology that focuses on the study of humans as biological organisms, encompassing aspects of human evolution, variation, and adaptation. It seeks to understand the physical and biological development of the human species, its origin, and the biological bases of human behavior.

Human Evolution and Primatology

A major component of biological anthropology is the study of human evolution.

This involves examining human fossils, genetic data, and the behavior of our closest relatives, the primates.

By comparing the anatomical, archaeological, genetic, and behavioral evidence, anthropologists can infer the evolutionary history and processes that have shaped our species.

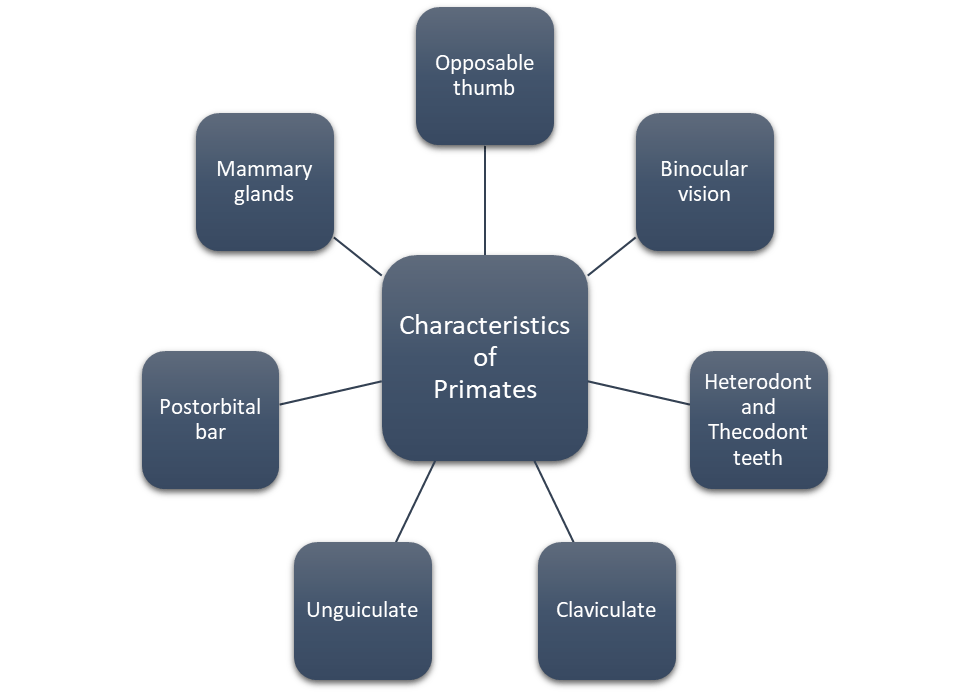

Primatology, the study of non-human primates, is a crucial aspect of understanding human evolution.

Primatologists study the behavior, biology, and ecology of living primates to gain insights into the evolutionary processes that shaped the natural history and adaptation of our species [5].

This involves the study of a wide variety of species, from lemurs and monkeys to gorillas and chimpanzees.

Human Variation and Adaptation

- Another fundamental aspect of biological anthropology is the study of human variation and adaptation.

- This involves understanding the genetic and physiological differences among human populations and how these differences have been shaped by environmental factors, including climate, diet, and disease.

- Human adaptation refers to the ways in which individuals and populations change biologically in response to specific environmental challenges.

- These can include short-term physiological adjustments, developmental changes, and long-term evolutionary modifications.

- By studying human variation and adaptation, biological anthropologists aim to understand the mechanisms through which our species has adapted to diverse environmental challenges, the consequences of these adaptations, and how they might influence our health and wellbeing.

Linguistic Anthropology

Linguistic Anthropology is a branch of anthropology that studies the role of language in social life. It considers how language shapes communication, forms social identity and group membership, organizes large-scale cultural beliefs and ideologies, and develops a common cultural representation of natural and social worlds.

Language in Culture and Society

- Understanding the role of language in culture and society is a central focus of linguistic anthropology.

- Language is not merely a system of communication; it is a medium through which individuals navigate and construct their social realities [6].

- Anthropologists consider language to be a cultural, social, and psychological phenomenon, and its study can provide a great deal of insight into the ways people think and how they relate to each other within a particular society [7].

- Anthropologists also study the way in which language reflects and constructs social identities and groups.

- Through the language choices people make in their interactions with others, they signal their social identity and group membership.

- In this way, language both reflects social structures and contributes to their construction and maintenance.

Archaeology

Archaeology, a major subfield of anthropology, is the scientific study of human life in the past through the recovery and analysis of material culture and environmental data that they have left behind, which includes artifacts, architecture, biofacts, and landscapes. It aims to understand human behavior and cultural patterns over different periods and in different geographic regions.

Prehistoric Archaeology

- Prehistoric archaeology is concerned with the period of human history before the advent of writing systems.

- Given the absence of written records, prehistoric archaeologists rely on other forms of evidence such as pottery, tools, and other artifacts, as well as features like hearths, postholes, and burials, to understand human life in prehistory.

- Prehistoric archaeology involves studying various aspects such as the origin and evolution of Homo sapiens, the hunter-gatherer era, the development of agriculture, and the rise of the first civilizations.

- The study of prehistory allows us to understand the long-term processes of human cultural and biological evolution.

Historic Archaeology

- Historic archaeology, on the other hand, studies the more recent past – the period after the invention of writing.

- This subfield deals with societies that have written records and involves the study of physical remains in conjunction with historical documents.

- Historic archaeology includes a broad range of topics such as colonialism, the development of modern states, the Industrial Revolution, and even the recent past.

- The combined use of artifacts and written documents in historic archaeology provides a more detailed and nuanced understanding of the past, often challenging the established narratives derived from historical accounts alone.

Methods and Techniques in Anthropology

Ethnography and Fieldwork

| Description | Methods | Example | |

| Ethnography | A qualitative research method used primarily in anthropology.· It involves detailed observation and documentation of a particular group, culture, or community. | The primary method of collecting ethnographic data is through fieldwork. This can include participant observation, interviews, focus groups, and other data collection methods. | Ethnographic research might involve living in a remote village to understand the culture and practices of the residents. |

| Fieldwork | The practice of collecting information outside of a laboratory, library, or workplace setting.· The researcher immerses themselves within the community they’re studying, often living among the people for extended periods. | Participatory observation is a primary method in fieldwork. It involves the researcher actively participating in the daily activities of the community, observing everything from major events to day-to-day activities. | A researcher might spend months in a community, participating in local events, rituals, and daily activities to gain a nuanced understanding of the culture. |

| Challenges and Ethics in Ethnographic Fieldwork | Ethnographic fieldwork often involves several challenges, including overcoming cultural barriers, establishing trust with the community, and coping with isolation and culture shock. | Ethical considerations are paramount in fieldwork, such as respecting cultural norms, ensuring informed consent, and maintaining the privacy and confidentiality of research participants. | An anthropologist may need to navigate complex cultural practices, or deal with language barriers and homesickness. They must ensure they have received informed consent from all research participants and respect their privacy and confidentiality. |

Comparative Method

The comparative method is a crucial tool in anthropology and other social sciences, providing a systematic approach to analyzing and understanding human societies and cultures. This research method involves comparing two or more cultures or phenomena to identify patterns, draw contrasts, and generate hypotheses about societal and cultural practices.

For example, an anthropologist might use the comparative method to examine different kinship systems across various societies. This could involve comparing matrilineal kinship structures in one society with patrilineal structures in another. Through this comparison, the researcher could identify similarities and differences, and gain insights into how different societal contexts influence kinship systems. The ultimate goal of the comparative method is to provide a more profound and nuanced understanding of human behavior and culture.

The comparative method extends beyond just cultures and societies. It can also be applied to compare languages (in linguistic anthropology), biological traits (in biological anthropology), or archaeological findings (in archaeology).

Archaeological techniques

Archaeological techniques have evolved significantly over time, combining traditional methods with modern scientific approaches. Here are some of the key techniques used in archaeology:

- Surveying: Before an excavation begins, archaeologists often conduct a survey of the area to locate sites of interest. This can involve walkover surveys, aerial surveys using drones or satellite imagery, and geophysical surveys using technologies like ground-penetrating radar (GPR) and magnetometers to detect buried features.

- Excavation: Excavation involves carefully digging and recording the positions of artifacts and features within a site. This can be a time-consuming process, as it’s important to preserve as much information as possible about the context in which each item is found. Excavation techniques include stratigraphic excavation, in which layers of soil are removed one at a time to reveal the sequence of occupation.

- Artifact Analysis: After artifacts are excavated, they’re cleaned, cataloged, and analyzed to gather information about their function, date, and style. This can involve techniques such as typology (classification based on physical characteristics), seriation (arranging objects in chronological order), and use-wear analysis (studying the marks on artifacts to determine how they were used).

- Laboratory Analysis: This can include a range of specialized techniques, such as radiocarbon dating to determine the age of organic materials, or stable isotope analysis to provide information about ancient diets and climates. DNA analysis can also be used to learn about ancient populations and their relationships to modern groups.

- Interpretation and Publication: After data is collected and analyzed, the results are interpreted and published so that others in the field can evaluate and build upon the findings. This can involve developing theories about the people who lived at the site, their culture, and their interactions with the environment and each other.

How to conduct Anthropological Research?

Interviews

Interviews provide insightful, in-depth accounts of the events that help us learn about the people, organizations, historical perspectives, the present, challenges, and pleasure. In order to learn more about one or more issues, a researcher will create a list of inquiries to ask when speaking with two or more persons [8].

Interviews allow ethnographic researchers the ability to engage with and learn more about the community or group they are examining. An interview may give insight on the roots of a cultural heritage or a common way of thinking by generating a spectrum of unique and shared experiences, thoughts, and memories. Interview questions might include, “What was anything that shocked you after joining your union?” or “Can you tell us about the first strike in which you took part?” Interviews may reveal insights on how your informants understand their position in the world and how they act in it.

Interviews, which can take many different forms, are a crucial research method for ethnographers because they provide a unique opportunity to enable your informants to explain and maintain their realities.

Surveys

Ethnographic surveys are just one type of research method used in anthropology; they do not entirely represent the study design. Just conducting a survey could result in inaccurate results, and if respondents are reluctant to share any information, they might lie on the survey. Additionally, different people may have different perspectives on the same problem, or other people’s comments occasionally don’t exactly match what they believe. Additionally, some data is omitted from surveys because it can be better obtained in other ways.

As a result, rather than relying solely on surveys for information, anthropologists use them to gather more data on specific topics. Imagine a circumstance where you are conducting in-depth interviews to obtain data. There are only so many interviews you can do; you can’t speak to everyone[9]. You could use a poll to see if the information gleaned from the interviews can be applied to the entire population.

Even though there are many distinct survey types, they may be categorized into two categories: questionnaires and interviews. An interview-based survey involves contacting a respondent over the phone or in person.

Archival research

A sort of study called “archive research” involves locating and gathering information from old records. These papers may be retained in possession of the organization (whether a government body, company, family, or other agency) that initially generated or accumulated the records, as well as in the custody of a subsequent entity (either through transfer or in-house archives). These records may also be kept in public places such as libraries and museums (via transfer or in-house archives).

A comparison of archive research to two other methods of primary research and empirical study, like fieldwork and experiment, and secondary research (done in a library or online), which entails discovering and reviewing secondary materials on the subject of inquiry, is important.

In addition, it is used in a wide range of humanities and social science fields, including literary studies, rhetoric, archaeology, sociology, human geography, anthropology, psychology, and organisational studies (in conjunction with related research approaches and methodologies). Archival research is essential to many types of original historical inquiry, including academic research.

Anthropology in the Modern World

Anthropology continues to play a crucial role in the modern world, providing a unique lens to understand and address contemporary issues. Anthropologists now study a wide range of topics, including urbanization, climate change, migration, public health, and technology. These studies offer valuable insights into how cultures adapt to changing circumstances and how these changes impact social structures, identities, and human relationships.

Modern anthropologists also often work in applied settings, using anthropological insights to design more effective interventions in fields such as development, education, healthcare, and conflict resolution. They work with policymakers, NGOs, businesses, and communities to address complex social and environmental challenges.

Anthropology and Globalization

Globalization has significantly impacted the field of anthropology. As societies become increasingly interconnected through trade, technology, migration, and media, anthropologists have been challenged to understand these processes and their effects on cultures, identities, and social relations.

Anthropologists study globalization from the ground up, looking at how global processes are experienced and interpreted by individuals and communities. They explore topics such as global flows of goods and people, the spread of global cultures and ideologies, the impacts of global economic policies on local communities, and the ways in which global issues like climate change are understood and addressed in different cultural contexts.

Furthermore, anthropologists have also been critical of the uneven impacts of globalization, highlighting issues of power, inequality, and cultural imperialism. They advocate for marginalized voices, and provide nuanced understandings of cultural diversity and resilience in the face of global change.

Role of Anthropology in Policy and Decision Making

Anthropology plays a crucial role in policy and decision making, providing important insights into human behavior, culture, and social structures that can help to design more effective and inclusive policies.

- Understanding Context: Policies do not exist in a vacuum; they operate within complex socio-cultural environments. Anthropologists can help to illuminate these contexts, offering deep insights into local customs, belief systems, social structures, and power dynamics. These insights can prevent potential cultural misunderstandings and ensure policies are relevant and acceptable to the communities they serve.

- Highlighting Diversity: Anthropology emphasizes cultural diversity, reminding us that policies should not take a one-size-fits-all approach. What works in one cultural or social context may not work in another. Anthropologists can help policymakers understand this diversity and design flexible policies that can be adapted to different cultural settings.

- Improving Participation: Anthropologists advocate for participatory approaches to policy-making, involving communities in the design, implementation, and evaluation of policies. This can increase policy effectiveness and ensure the needs and perspectives of marginalized groups are taken into account.

- Uncovering Hidden Assumptions: Anthropologists are trained to question assumptions and uncover taken-for-granted beliefs. This can help to challenge policy discourses that may overlook or marginalize certain perspectives.

- Monitoring and Evaluation: Anthropologists can also contribute to monitoring and evaluation of policies, using ethnographic methods to understand how policies are being implemented, how they are affecting people’s lives, and how they can be improved.

Influential Anthropologists and Their Contributions

Franz Boas: The Father of American Anthropology

Franz Boas (1858–1942), a German-born American anthropologist, is often called the “Father of American Anthropology” for his pioneering role in establishing anthropology as a recognized academic discipline in the United States and his profound influence on the field.

Bronisław Malinowski: The Father of British Anthropology

Bronisław Malinowski (1884–1942) is widely recognized as the father of British social anthropology. Born in Poland, Malinowski had a significant impact on the development of anthropology as a discipline, especially in the United Kingdom.

Margaret Mead: Culture and Personality

Margaret Mead (1901–1978), a student of Franz Boas and one of the most renowned anthropologists of the 20th century, made significant contributions to the field of anthropology, particularly in the areas of culture and personality.

Clifford Geertz: Interpretive Anthropology

Clifford Geertz (1926–2006) was an influential American anthropologist known for his work in symbolic and interpretive anthropology. His pioneering approach to ethnography has left a significant impact on the field of anthropology and the social sciences more broadly.

Critiques of Anthropology

In general, anthropological criticism situated the production, dissemination, and consumption of literature within the standards and customs of human civilizations. Throughout the 20th century, there have been more obstacles to the idea of a focused problem and a reliable body of information, making such an attempt weaker. One observer claims that it is being looked into because of its history of supporting prejudice and slavery as well as its openness to colonial power. Since “any emphasis excludes,” according to a different participant, there is no political neutral method of international interpretation. These topics have attracted the attention of notable philosophers like Jean-Paul Sartre, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Edward Said, and Jacques Derrida.

Anthropological criticism attracted a lot of interest in the early 20th century. The Golden Bough was used by the Cambridge school of classical anthropology, which adhered to Sir James Frazer’s beliefs, as a standard for assessing Greek play. According to the findings of this loosely related group of scholars and writers known as the “ritualists” (Jane Harrison, F. M. Cornford, A. B. Cook, and Gilbert Murray), Greek theater had a prehistory of myth and ritual. People mistakenly believed that classical plays represented far earlier, pagan ceremonial practices as a result of this.

Postmodern criticisms of the discipline

The main argument used in postmodern critiques of ethnography is that there can never be true objectivity and that, consequently, the scientific method cannot be fully applied. The inability of an anthropologist to link the context of inquiry and the context of explanation, for instance, is how Isaac Reed characterizes the postmodern threat to the objectivity of social science.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, several anthropologists, particularly Crapanzano and Rabinow, started to seriously doubt the importance of fieldwork. The criticism of anthropologists’ interpretation and portrayal of the Other—basically, how they engaged in “writing culture”—had grown into a significant epistemological issue by the middle of the 1980s, which Reed refers to as the “postmodern”[10].

Modernity is attributed to the Renaissance. The modern world is characterized by increasing economic and administrative rationality as well as social fragmentation. This argument essentially developed in the context of the establishment of the capitalist state. Boyne and Rattansi describe modernity as having two sides: “the gradual merger of scientific objectivity and politico-economic rationality, reflected in disturbing visions of unalleviated existential crisis.” Questioning the basis of prior knowledge is the primary act of modernity despair.”[11]

Being postmodern is a condition or scenario known as postmodernity. Postmodernism is literally “after modernity,” which makes sense. It speaks of the impending or actual dissolution of modernity’s social structures.[12]

Ethnocentrism and cultural imperialism

Anthropology is commonly misunderstood in the public domain and popular imagination since it is a broad-based social science study that combines science and the humanities. In many regions of the globe, it has been condemned to the furthest edges of society.

Interdisciplinary courses that are administratively convenient at universities and research institutions often feature sociology as one of the intellectual and public life components. Many areas of Sub-Saharan Africa have vilified anthropology because of its supposed historical connections to European colonization (2006) Ntarangwui, Mills, and Babiker Due to sociocultural anthropology’s image as the “handmaiden of colonialism,” some sociocultural anthropologists have endeavored to appear as sociologists, geographers, or other broad social scientists.

Liberal and radical opponents of imperial authority were social anthropologists throughout the colonial period. Overall, though, it is apparent that the development of European colonialism opened the door for cross-cultural research, which gave birth to the current subject of anthropology. Anthropology has long fostered inquiry into the political features of the many varied civilizations that make up the planet. Renewing and Decolonizing Anthropology

Critiques of the fieldwork method

A professional investigator’s standard fieldwork results in a standard ethnography, which includes descriptions of repeating behavioral patterns, personal information, family norms and conduct, economic activities, common belief systems, and rituals.

However, these same incentives frequently lead ethnographers to ignore certain fascinating research fields. The approach and tools of field study are inherently insufficient for analyzing and comprehending mundane, incomprehensible, and asocial cultural realities. They don’t help people choose the questions that are relevant to their culture. Rarely is the significance of the study’s findings for the research subjects taken into account. Above all, traditional fieldwork does not offer a platform from which to deeply and critically examine culture and society..

These faults wouldn’t matter if anthropologists didn’t assert that their ethnographies provide full accounts of sociocultural reality and explanations of it. These arguments are founded first on fieldwork and second on the scientific viability of anthropological literature. Recent discussion has centered on issues relating to the status of writing, influenced by postmodernist philosophy (for instance, Clifford and Marcus, 1986).

The epistemological underpinning of fieldwork in general, as opposed to the falsification of its findings, has nevertheless been assumed. Despite the efforts of even the most passionate supporters, participant observation and interviewing continue to be the major techniques of ethnographic research (such as Marcus and Fischer in 1986, Clifford in 1988, and Rabinow in 1977).

The Future of Anthropology

The future of anthropology looks promising yet fraught with challenges, as anthropologists navigate a rapidly changing world. From technological advancements and globalization to issues of climate change, inequality, and political upheaval, anthropologists find themselves facing complex new questions about the human experience.

Challenges Facing Anthropology

- Decolonizing Anthropology: Anthropology has been criticized for its historical ties to colonialism, and there is a growing movement to “decolonize” the discipline by challenging its Eurocentric biases, diversifying its perspectives, and recognizing the knowledge of indigenous and marginalized peoples.

- Ethics and Representation: Anthropologists are constantly grappling with ethical issues related to conducting fieldwork and representing other cultures. This includes issues of informed consent, privacy, and the potential for exploitation or harm.

- Interdisciplinary Collaboration: As the problems facing humanity become more complex, anthropologists are increasingly called upon to collaborate with other disciplines, from ecology and public health to computer science and engineering. While this can yield rich insights, it also poses challenges of communication and methodological integration.

Emerging Areas of Study

- Digital Anthropology: As our lives become increasingly digital, anthropologists are studying how technology shapes our identities, relationships, and societies. This includes everything from online communities and virtual reality to the impact of artificial intelligence and big data on human life.

- Climate Change and Anthropology: Anthropologists are making vital contributions to understanding and addressing climate change. They are studying how climate change impacts diverse cultures and how cultural practices can contribute to resilience and adaptation. They are also investigating the social and cultural dimensions of climate politics and policy.

- Medical Anthropology: This subfield focuses on the intersection of health, medicine, and culture, examining how social and cultural factors influence health outcomes, how people understand and respond to illness, and how medical practice itself is shaped by cultural norms and social structures.

Conclusion

In conclusion, anthropology offers a unique lens through which to study the diversity of human cultures and societies. Through its various subfields, such as archaeology, biological anthropology, linguistic anthropology, and cultural anthropology, anthropologists have contributed significantly to our understanding of human evolution, behavior, and interaction. As anthropologists continue to grapple with contemporary issues such as globalization, climate change, and social inequality, it is clear that the field will remain an essential discipline for understanding the complex and dynamic nature of humanity. The contributions of anthropology are invaluable to our collective knowledge of human existence and will undoubtedly continue to shape our understanding of the world in the years to come.

Notable Anthropologists

- Franz Boas

- Margaret Mead

- Ruth Benedict

- Bronislaw Malinowski

- Claude Levi-Strauss

- Clifford Geertz

- Louis Leakey

- Lewis Henry Morgan

- Edward Sapir

- Edward Burnett Tylor

- James George Frazer

- Jane Goodall

References

[1] Stanford, C. B. (2012). Biological Anthropology: The Natural History of Humankind. PHI Learning Private Limited.

[2] Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures: selected essays. Basic books.

[3] Herskovits, M. J. (1973). Cultural relativism: Perspectives in cultural pluralism. Vintage.

[4] Marcus, G. E. (1998). Ethnography through thick and thin. Princeton University Press.

[5] Napier, J. R., & Napier, P. H. (1985). The natural history of the primates. British Museum (Natural History).

[6] Sapir, E. (1921). Language: An Introduction to the Study of Speech. Harcourt, Brace and Company.

[7] Duranti, A. (1997). Linguistic Anthropology. Cambridge University Press.

[8] Manifold @CUNY. (n.d.). In Manifold @CUNY. https://cuny.manifoldapp.org/read/untitled-fefc096b-ef1c-4e20-9b1f-cce4e33d7bae/section/514ee90c-918e-4f9d-8122-59a3f858b135.

[9] Manifold @CUNY. (n.d.). In Manifold @CUNY. https://cuny.manifoldapp.org/read/untitled-fefc096b-ef1c-4e20-9b1f-cce4e33d7bae/section/514ee90c-918e-4f9d-8122-59a3f858b135

[10] Retrieved from https://anthropology.ua.edu/theory/postmodernism-and-its-critics.

[11] Boyne, Roy and Ali Rattansi (1990) The Theory and Politics of Postmodernism: By Way of an Introduction. In Roy Boyne and Ali Rattansi (eds), Postmodernism and Society (pp. 1-45). London: MacMillan Education LTD.12. Retrieved from https://anthropology.ua.edu/theory/postmodernism-and-its-critics

[12] Retrieved from https://anthropology.ua.edu/theory/postmodernism-and-its-critics