AI Answer Evaluation Platform Live Now. Try Free Answer Evaluation Now

Fieldwork in Anthropology

Fieldwork is a fundamental methodology in anthropology that involves immersing oneself in a specific community or cultural setting to conduct firsthand research. It encompasses a range of activities, including participant observation, interviews, and data collection, with the goal of gaining a comprehensive understanding of the social, cultural, and environmental dynamics at play within a given context [1]. By engaging directly with the people and practices being studied, fieldwork enables anthropologists to generate rich, context-specific data that contributes to the broader understanding of human societies.

Importance of Fieldwork in Anthropology

- Fieldwork holds significant importance in the field of anthropology due to its ability to provide nuanced insights into the complexities of human behavior, cultural practices, and social dynamics.

- Unlike other research methodologies that rely solely on secondary sources or quantitative data, fieldwork allows researchers to explore the intricacies of human experiences and meanings from an insider’s perspective.

- One key aspect of fieldwork is participant observation, which involves active participation in the daily lives and activities of the community being studied. This method allows researchers to observe and document cultural practices, rituals, and social interactions in their natural context [2].

- For example, in studying a traditional healing ceremony, an anthropologist might not only observe the ritual but also engage in conversations with healers and patients, gaining a deeper understanding of the symbolic meanings and social significance of the practice.

- Fieldwork also facilitates the identification and analysis of social structures, power dynamics, and cultural norms within a community [3].

- By spending an extended period of time in the field, anthropologists can observe changes and transformations over time, uncovering the historical and contextual factors that shape social life.

- Moreover, fieldwork allows anthropologists to challenge ethnocentric biases and stereotypes by promoting cultural relativism. Through first-hand experiences and interactions, researchers gain a deep appreciation for the diversity and complexity of human societies.

- This cross-cultural understanding enhances empathy and helps bridge gaps between different communities, fostering intercultural dialogue and respect.

Preparing for the Field

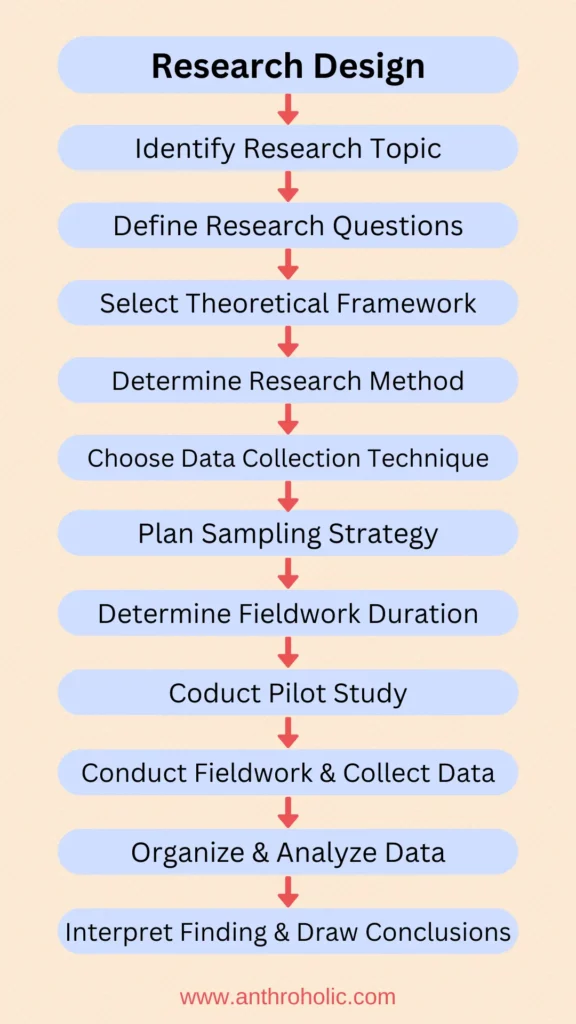

Research Design and Objectives

Before embarking on fieldwork, anthropologists need to carefully design their research and establish clear objectives. Research design involves formulating research questions, selecting appropriate methods, and determining the scope and boundaries of the study [4]. Anthropologists must consider the theoretical frameworks they will employ, as well as the practical considerations of data collection and analysis.

The research design should align with the specific goals of the study, which can range from exploring cultural practices and social dynamics to investigating specific phenomena within a community. For example, a researcher might be interested in understanding the impact of urbanization on indigenous communities’ traditional livelihood strategies.

Selecting the Field Site

- Selecting an appropriate field site is a critical aspect of fieldwork.

- The field site should be chosen based on the research objectives, ensuring that it provides access to the cultural group or community being studied [5].

- The site should be representative of the broader cultural context, allowing researchers to explore relevant social and cultural phenomena.

- Field sites can vary widely, from remote villages to urban neighborhoods or specific institutions.

- For instance, an anthropologist studying gender dynamics in a rural community might select a village known for its distinct gender roles and traditions.

Building Relationships and Gaining Access

- Building relationships with the community and gaining access to the field site are essential for successful fieldwork.

- Anthropologists must establish trust, rapport, and reciprocity with community members, as this facilitates access to cultural knowledge and participation in daily activities [6].

- Anthropologists employ various strategies to build relationships, such as engaging in informal conversations, participating in community events, and seeking permission and guidance from community leaders or gatekeepers.

- Respect for local customs and traditions is crucial in building trust and establishing credibility within the community.

- For example, an anthropologist studying traditional healing practices may seek permission from local healers to observe and document their rituals.

- By actively involving themselves in the community’s activities, anthropologists can demonstrate their genuine interest and commitment to understanding the community’s perspectives and experiences.

Establishing Rapport and Building Trust

Building Relationships with Informants

- In anthropological fieldwork, building relationships with informants is crucial for gaining access to cultural knowledge and understanding the nuances of the community being studied.

- Establishing rapport involves developing a sense of trust, respect, and reciprocity with informants, which facilitates open communication and collaboration.

- Anthropologists employ various strategies to build relationships, such as engaging in informal conversations, participating in community activities, and actively listening to the experiences and perspectives of informants

- For example, during fieldwork in a fishing community, an anthropologist may spend time talking to local fishermen, joining them in their daily routines, and showing genuine interest in their work and traditions. These interactions lay the foundation for building trust and rapport.

Navigating Power Dynamics

- Power dynamics within the research process must be carefully considered in anthropological fieldwork.

- Researchers must be mindful of their own positionality and the potential power imbalances that exist between the researcher and the community being studied.

- Anthropologists strive to mitigate these power differentials by adopting an attitude of humility, recognizing the expertise and agency of informants, and engaging in collaborative research approaches.

- They aim to share decision-making power, provide opportunities for informants to voice their perspectives, and ensure that their research benefits the community being studied.

- For instance, in researching indigenous land rights, an anthropologist may work closely with community leaders and engage in participatory methods that empower community members to actively shape the research process.

- By acknowledging and addressing power dynamics, researchers can foster a more equitable and ethical fieldwork experience.

Establishing Cultural Sensitivity

- Cultural sensitivity is essential for conducting anthropological fieldwork ethically and respectfully.

- Anthropologists should demonstrate an understanding of and respect for the cultural norms, values, and practices of the community being studied [1].

- Cultural sensitivity involves adopting a reflexive approach, critically examining one’s own biases, assumptions, and preconceived notions. It requires researchers to actively listen, learn, and adapt to the cultural context in which they are working.

- Sensitivity also extends to ensuring informed consent, protecting confidentiality, and safeguarding the cultural heritage and intellectual property rights of the community.

- For example, when studying a religious ceremony, anthropologists should familiarize themselves with the cultural significance of the rituals, seek permission from community members, and adhere to any protocols or restrictions associated with the event. This demonstrates respect for the cultural practices and beliefs of the community.

Fieldwork Challenges

Loneliness and Isolation

- Loneliness and isolation are common challenges faced by anthropologists during fieldwork, particularly when conducting research in remote or unfamiliar settings.

- The immersive nature of fieldwork often involves being separated from familiar social networks, family, and friends [7].

- This sense of isolation can lead to feelings of loneliness, homesickness, and emotional distress.

- For example, an anthropologist conducting research in a remote village in the Amazon rainforest may experience a profound sense of isolation due to the physical distance from their support network.

- To address this challenge, researchers may engage in self-care strategies, maintain regular communication with loved ones, and seek social connections within the community being studied.

Health and Safety Concerns

- Fieldwork often involves working in unfamiliar and sometimes challenging environments, which can pose health and safety risks for anthropologists.

- These risks may include exposure to infectious diseases, environmental hazards, or political instability.

- It is essential for researchers to prioritize their well-being and take appropriate precautions to minimize health and safety risks.

- For instance, conducting fieldwork in regions with endemic diseases requires researchers to adhere to proper vaccination protocols and follow hygiene practices. Researchers may need to consult local healthcare professionals, obtain travel insurance, and stay informed about any potential risks or safety advisories in the field site.

Emotional Toll and Personal Well-being

- Engaging in fieldwork can have an emotional toll on anthropologists due to the intensive and immersive nature of the research process.

- Researchers may encounter distressing or emotionally challenging situations, such as witnessing inequality, poverty, or social injustices.

- These experiences can affect the emotional well-being and mental health of researchers.

- For example, an anthropologist studying the impact of conflict on displaced communities may face emotional distress when listening to traumatic experiences shared by individuals. To address this challenge, researchers may engage in self-reflection, seek support from colleagues or mentors, and consider accessing mental health resources available in the field or upon returning from the field.

Data Collection and Analysis

Collecting Rich Ethnographic Data

- Collecting rich ethnographic data is a fundamental aspect of anthropological fieldwork.

- Ethnographic data encompasses a wide range of information, including observations, interviews, conversations, and cultural artifacts.

- Anthropologists aim to capture the complexity and depth of social and cultural phenomena by employing various data collection techniques.

- For instance, through participant observation, anthropologists actively engage in the daily activities and routines of the community being studied. By immersing themselves in the cultural context, they can observe and document behaviors, rituals, and interactions, capturing the subtleties and nuances of the social dynamics.

Documentation Techniques: Note-taking, Audio/Video Recording

- Note-taking is a commonly used technique for documenting observations, conversations, and field notes during fieldwork. It allows researchers to capture real-time information and record their impressions and reflections. Notes can be taken in various formats, such as field diaries, journals, or digital platforms.

- In addition to note-taking, audio and video recording have become valuable tools for capturing and preserving ethnographic data. These techniques provide researchers with the ability to review and analyze detailed interactions, expressions, and cultural practices that may not be easily captured through written notes alone.

- For example, an anthropologist studying traditional music performances may use audio or video recording to document the melodies, rhythms, and accompanying movements, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the cultural context and the significance of music in the community.

Data Coding, Transcription, and Analysis

- Once the data is collected, anthropologists engage in data coding, transcription, and analysis to identify patterns, themes, and insights.

- Coding involves categorizing and organizing the data according to themes or concepts that emerge from the research [8].

- Transcription entails converting audio or video recordings into written text, facilitating the analysis process.

- The analysis phase involves interpreting and making sense of the data in relation to the research questions and theoretical framework.

- Anthropologists employ various analytical approaches, such as thematic analysis, content analysis, or grounded theory, depending on the nature of the research.

- For instance, in analyzing interview data, researchers may identify recurring themes or categories that represent participants’ perspectives and experiences. These themes can then be explored in-depth, revealing insights and contributing to the overall understanding of the research topic.

Reflexivity and Positionality

The Role of the Researcher

- In anthropological research, the role of the researcher is crucial and requires self-reflection and awareness.

- Anthropologists recognize that their own positionality, including their personal backgrounds, cultural biases, and social identities, can influence the research process and outcomes.

- Understanding and acknowledging the researcher’s role allows for a more nuanced interpretation of the data.

- For example, a researcher who comes from a privileged background might need to critically examine how their social positionality affects their interactions and perceptions within a marginalized community. By recognizing their positionality, anthropologists can navigate potential power dynamics and engage in more ethical and inclusive research practices.

Recognizing and Addressing Biases

- Anthropologists strive to recognize and address their own biases during fieldwork.

- Bias can manifest in various forms, such as cultural, gender, or racial biases, and can influence the interpretation and representation of research findings.

- Awareness of biases is essential for conducting unbiased and objective research.

- For instance, a researcher conducting a study on gender roles within a specific community must be aware of their own gender biases and how they may influence their observations and interpretations. By actively questioning and critically reflecting on biases, anthropologists can strive for a more nuanced and accurate understanding of the culture being studied.

Reflexive Fieldwork Practices

- Reflexivity is a key aspect of anthropological fieldwork, emphasizing the importance of critically reflecting on one’s own position, assumptions, and biases throughout the research process [9]

- Reflexivity involves ongoing self-awareness and examination of how the researcher’s presence and actions impact the research context.

- For example, during fieldwork, an anthropologist may engage in reflexive practices by regularly journaling and reflecting on their experiences, interactions, and emotional responses. This process allows for a deeper understanding of the researcher’s own influence on the research process and promotes transparency in ethnographic representation.

- Reflexivity also extends to engaging with the community being studied. Anthropologists may seek feedback and input from community members, incorporating their perspectives and interpretations to ensure a more collaborative and accurate representation of their culture.

Challenges in Contemporary Fieldwork

Technological Advancements and Ethical Considerations

- Technological advancements have significantly impacted anthropological fieldwork, presenting both opportunities and challenges.

- The use of digital tools, such as smartphones, cameras, and social media platforms, has expanded the range of data collection methods and increased access to remote communities.

- However, these advancements also raise ethical considerations related to privacy, informed consent, and the potential exploitation of data.

- For example, the use of social media platforms for data collection requires careful consideration of privacy concerns and the potential impact on the participants’ lives. Researchers must navigate the ethical implications of obtaining consent for online interactions and ensure the responsible and respectful use of the data collected [10].

Political and Social Instability

Conducting fieldwork in politically or socially unstable contexts poses unique challenges for anthropologists. Political conflicts, social unrest, or volatile environments can hinder research activities, limit access to communities, and create safety concerns for both researchers and participants. In such contexts, researchers must carefully assess the risks involved and take necessary precautions to ensure the well-being and safety of themselves and the community being studied. Collaboration with local partners or organizations can provide valuable insights and support in navigating these challenges.

Indigenous Rights and Collaborative Research

Engaging in research with indigenous communities raises important ethical and political considerations. Anthropologists must recognize and respect indigenous rights, including the right to self-determination and control over their cultural heritage. Collaborative research approaches that involve active participation and shared decision-making with indigenous communities have emerged as an ethical response to these challenges.

For example, anthropologists working with indigenous communities may engage in collaborative research that prioritizes the community’s goals, knowledge, and perspectives. This approach respects indigenous protocols, ensures the equitable distribution of benefits, and fosters meaningful and mutually beneficial relationships.

Conclusion

Reflecting on the Fieldwork Journey

The fieldwork journey in anthropology is a transformative and enlightening experience for researchers. It involves immersing oneself in the lives and cultures of the communities being studied, navigating challenges, building relationships, and collecting rich data. Reflecting on this journey allows anthropologists to gain a deeper understanding of their research, personal growth, and the impact of their work.

During the fieldwork journey, researchers encounter various situations that challenge their assumptions, broaden their perspectives, and push them to critically reflect on their own biases and positionality. This process of self-reflection fosters a more nuanced and empathetic approach to understanding and representing the communities being studied.

For example, through the fieldwork journey, an anthropologist may confront their own cultural biases and challenge preconceived notions about certain practices or beliefs. This reflective process enhances the researcher’s ability to engage with cultural differences in a respectful and open-minded manner.

Contributions of Fieldwork to Anthropological Knowledge

Fieldwork is the foundation of anthropological knowledge, providing rich and context-specific data that contributes to the broader understanding of human societies and cultures. By immersing themselves in the field, anthropologists gain firsthand insights into the complexities of social, cultural, and environmental dynamics.

The data collected during fieldwork offers detailed accounts of cultural practices, rituals, social interactions, and power dynamics, among other phenomena. These qualitative and nuanced data contribute to the development and refinement of anthropological theories, concepts, and methodologies.

For instance, fieldwork-based studies on kinship systems, religion, economic practices, or gender dynamics have deepened our understanding of these phenomena across diverse cultural contexts. The richness and depth of fieldwork data provide anthropologists with a unique vantage point for analysis and interpretation.

Furthermore, fieldwork contributes to cross-cultural understanding, challenging ethnocentric perspectives and promoting cultural relativism. By immersing themselves in different cultural settings, anthropologists gain a deeper appreciation for the diversity and complexity of human societies. This understanding fosters intercultural dialogue, respect, and empathy.

FAQs about Fieldwork in Anthropology

References

[1] Hammersley, M., & Atkinson, P. (2019). Ethnography: Principles in practice. Routledge.

[2] Malinowski, B. (1922). Argonauts of the Western Pacific: An account of native enterprise and adventure in the archipelagoes of Melanesian New Guinea. Routledge. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/55822/55822-h/55822-h.htm

[3] Clifford, J., & Marcus, G. E. (1986). Writing culture: The poetics and politics of ethnography. University of California Press.

[4] Bernard, H. R. (2018). Research methods in anthropology: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Rowman & Littlefield.

[5] Bryman, A. (2018). Social research methods. Oxford University Press.

[6] Van Maanen, J. (2011). Tales of the field: On writing ethnography. University of Chicago Press.

[7] Pink, S., Morgan, J., & Dainty, A. (Eds.). (2013). Doing sensory ethnography. Sage

[8] Saldaña, J. (2015). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage.

[9] Rabinow, P. (1977). Reflections on fieldwork in Morocco. University of California Press.

[10] Boellstorff, T., Nardi, B., Pearce, C., & Taylor, T. L. (2012). Ethnography and virtual worlds: A handbook of method. Princeton University Press.