AI Answer Evaluation Platform Live Now. Try Free Answer Evaluation Now

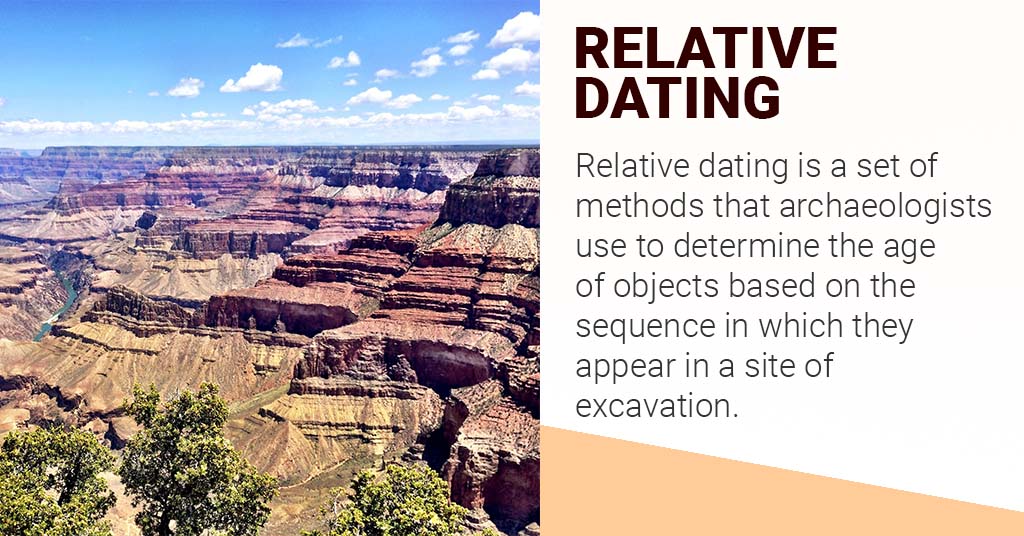

Relative Dating

Relative dating is a set of methods that archaeologists use to determine the age of objects based on the sequence in which they appear in a site of excavation. This technique does not focus on precise dates but instead on the principle that older objects appear in lower layers of the ground and more recent objects occur closer to the surface in a given site. As a result relative dating almost indefinitely coincides with the concept of stratigraphy.

Nicholas Steno’s Laws of Stratigraphy as proposed in 1669 –

- Law of superposition – The aforementioned temporal deposition of layers encase the artifacts or remains in a sequential order from bottom to the top.

- Lateral continuity – Continuation of deposited strata across a lateral direction unless erosion or valleys break the continuity.

These are strictly geological principles that in many ways laid the foundation of relative dating in archaeology. Also known as Indirect dating, this technique was employed by early archaeologists to transfix excavated artifacts according to their age, origin and occurrence subjectively to a specific site.

Origin of Relative Dating

It is difficult to imagine archaeological dating without precise dates today, as we have adopted high standards of technology and radiometric dating to assign ages to excavated remains. However, stratigraphic representation has been a longstanding practice in archaeological pursuits. General Pitt Rivers used the method while excavating Cranborne Chase way back in the 1880s. Similar techniques were used by Heinrich Schliemann in 1873 while excavating Troy. So one can infer that soil sediments were thought of as chronological units which encompassed the artifacts of their contextual time. British archaeologist Leonard Woolley had also employed stratigraphical drawings in his excavations at Ur (Mesopotamia). These archaeologists were acutely interested in investigating the scope and expanse of their sites rather than the precise dates in which these cultures occurred. As a result, relative dating found its place in mainstream archaeology.

Purpose of Relative Dating

The main objective of relative dating was to give a broad understanding of excavated remains like fossils or artifacts and their temporal relationship with each other. The purpose was to assign time periods based on typology and technology rather than specific dates. It is largely a qualitative study of assemblages in an attempt to reconstruct the development of material cultures as they evolved in specific regions. The abundance of relative dating studies have allowed for comparing and analyzing human cultures globally, based on where they occurred in the stratigraphical context (cross-dating). Because specific numerical values are out of the question, relative dating paves way for a more holistic understanding of cultural evolution via identical artifacts found in various geographical regions. This is an anthropological study that will be discussed in the last section of this article.

Key Perspectives

The principles and methods in stratigraphy have been discussed owing to its importance in relative dating purposes. Below are some theoretical concepts that have been developed due to the nature of chronological sequence and the implication it has from a social anthropological standpoint.

Stratigraphy in Relative Dating

Socio-cultural aspects

JJ Worsaae used stratigraphy to prove the Three Age System in 1846 based on the occurrence of tool technology in different layers of sediments. This is key in understanding the socio-cultural evolution of human societies. Additionally, relative dating provides impetus for studying how cognition of human beings must have developed over time as highly complex artifacts like hafting microlith tools and peculiar pottery designs occur in the soil layers above those containing fairly simple and basic tool types (cleavers, handaxes and core tools). In many instances, the residential structures found in the upper layers are highly advanced with intelligent designs and housing patterns as opposed to the bottom layers. Moreover, the infrastructure in early phases of few sites like Harappa is quite simplistic while mature phases point towards a highly urbanized spatial expansion. [1]

Societal changes are also denoted by the design of infrastructures in different layers of strata. For example, in the upper layers of Indus Valley Civilization or certain Chalcolithic settlements like Inamgaon[2] we see a variation in housing sizes and patterns (as opposed to lower layers). Similarly in Egyptian sites of Naqada sequence, the upper layers uniquely contain differentiated graves in cemeteries (high status burials)[3]. This points to a more hierarchical form of society than the previous phases. It also shows how past cultures became more economically complex with each gradual phase. Anthropologists study such aspects of relative dating to infer past socio-cultural progression.

Typo-technology and Raw material

With the advent of the three age system, much consideration is given to the chronological sequence and morphology of tool technology in archaeological assemblages. Relative dating can help assign tool typology to lifestyles of past human cultures. For example, the earlier stone tools are associated with hunter gatherer and foraging time periods. The findings of more complex tools like microliths, blades and lunates point to developed hunting techniques along with neolithic farming and so on. The lateral continuity of raw materials used to make these tools can also give us an understanding of their availability in a certain time based on where they are placed in stratigraphic layers. Additionally, while excavating Mehrgarh, a site in Pakistan, the raw materials like flint occur in advancing forms in the upper layers showing a change in intuition, precision and understanding about manufacturing stone tools. [4]

Biological Remains

Stratigraphic placement of bones and animal fossils can also be used to relatively date artifacts found in the same layers. For example, if an artifact is found along with the fossilized bones of an extinct organism then that artifact is from the time period when the organism existed. This kind of study is done in paleontology labs. For this purpose, radiometric dating is not required as it depends on the location of the fossils in a given sequence.

Cross-Dating in Relative Dating

Cross-dating is a technique employed by archaeologists to relatively date consistent objects in the same site or sites in different regions. This method uses the principles of consistency, contemporaneity and correlation.[5] It holds the notion that generally similar objects found in a sequence of layers in different locations are contemporaneous (synchronic). This is a parallel correlation type of method that does not have a precise mathematical methodology [6] but helps immensely in placing objects or remains within a chronology. For the purpose of correlation, at least one parameter needs to be utilized when correlating two different sites. For example, in 1890s William Flinders Petrie considered the pottery sherds found from his work in Egypt to relatively date early (Greek) Minoan and Aegean civilizations. This type of relative dating requires a single civilization to be studied beforehand, however absolute dating was not available at the time and this work was considered to be groundbreaking in the field of archaeology. Cross-dating has its limitations in that it depends solely on proper knowledge about the reference-site. Such types of relative dating can have problems when the nature of evidence is scarce. This can result in issues regarding interpretation.

Sequence Dating (Seriation)

Sir William Matthew Flinders-Petrie is such a stalwart in early archaeology that even sequence dating as a technique of relative dating is accredited to him. He employed this method during his work in Egypt in 1880 and helped develop the methodology of seriation in archaeology. It basically includes the chronological arrangement of assemblages according to their typology and style. Flinders-Petrie discovered the sequence of Upper Egypt graves using the nature of artifacts placed inside them.

This relative dating, also pertains to tracking cultural trends of artifacts. Examples in pottery include shape, handle-type, size of the base, decorations, motifs etc. Such features point to specific trends in specific timelines. Based on their abundance they can be arranged in a sequential order to denote which styles came before and which came after. Often, the availability of the same level of frequency in a different site could mean that the two layers are contemporaneous. This was first pioneered by anthropologist Alfred Kroeber in 1916 as ‘Frequency Seriation’. And this did not rely on superposition or stratigraphy, but instead on the quantification of trends.[7]

This type of method suffers from the pre-axiomatic assumption that stylistic inferences are enough to denote cultural shifts in different parts of the world. This can often produce unilinear studies and such type of relative dating can be misleading. Additionally, cultural groups in seriation can be restricted to having similar genes, localities and traditions. Hence, the applicability of such techniques is currently doubtful, if not inordinately conditional.[8] These limitations, in the face of modern factual absolute dating, have rendered seriation obsolete.

Discussion

As we can see, relative dating is largely a theoretical domain within archaeology. The absence of numerical values helps in anthropological interpretation of past cultures in relation with their economy, tradition and in prehistory – cognition. Relative dating was a key facet in early archaeology when the time-based classification of antiquities began to gain importance. Absolute dating provides dates, but relative dating speaks to the broad generalized aspects of cultural evolution, development of human cognition, changes in subsistence and so on. Hence, this article has focused on key perspectives rather than just the methodology. Availability of literature related to relative dating in archaeology is scarce, but the concept has been explored by scholars like A.L Kroeber, John Rowe, Colin Renfrew and many more. This suggests that as much as precise dates give clear markers in the chronology of humankind, we can rely on theoretical concepts for parts of history where absolute dates are unimportant, if not unnecessary. With that in mind, the shortcomings of all the methods have also been discussed as it showcases the development of archaeology as a scientific study in the recent past.

References

[1] Possehl, G. L. (2000). “The Mature Harappan Phase”. Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute. 60/61: 243–251

[2] Excavations at Inamgaon. India: Deccan College Post Graduate and Research Institute, 1986.

[3]Kohler, Timothy A., and Michael E. Smith, eds. 2018. Ten Thousand Years of Inequality: The Archaeology of Wealth Differences. N.p.: University of Arizona Press.

[4] Marcon, V. (n.d.) “Technical innovations and conceptual changes in the lithic debitage of the aceramic Neolithic of Mehrgarh (Baluchistan,Pakistan)’, in E. M. Raven & G. L. Possehl (eds.) South Asian Archaeology 1999. Groningen.

[5] Thomas Carl Patterson (1963). Contemporaneity and Cross-Dating in Archaeological Interpretation. American Antiquity, 28(3), 389–392. doi:10.2307/278283

[6] Levy, E., Piasetzky, E. & Fantalkin, A. Archaeological cross dating: a formalized scheme. Archaeol Anthropol Sci 13, 184 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-021-01371-8

[7] Lyman, R., Wolverton, S., & O’Brien, M. (1998). Seriation, Superposition, and Interdigitation: A History of Americanist Graphic Depictions of Culture Change. American Antiquity, 63(2), 239-261. doi:10.2307/269469

[8] Robert C. Dunnell (1970). Seriation Method and Its Evaluation. American Antiquity, 35(3), 305–319. doi:10.2307/278341

Additional Reading

Gebhard, C., Dickerson, D., Gebhard, P., Gordon, A., Griffin, J.B., Ford, J.A., … Phillips, P. (2010). Archaeological Survey in the Lower Mississippi Alluvial Valley, 1940–1947. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press.

Madsen, Mark E. and Lipo, Carl P., “Measuring Cultural Relatedness Using Multiple Seriation Ordering Algorithms” (2016). Anthropology Faculty Scholarship. 15.

Hirst, K. Kris. “Archaeological Dating: Stratigraphy and Seriation.” ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/archaeological-dating-stratigraphy-and-seriation-167119 .

![The Cambrian Period, roughly 541 to 485.4 million years ago, marks a significant era in the history of life on Earth[1]. During this time, a remarkable explosion of diversity occurred, with the first appearance of many multicellular organisms and early forms of many major groups of animals alive today.](https://anthroholic.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Cambrian-Era-in-Geological-Time-Scale-in-Archaeology-300x157.webp)