AI Answer Evaluation Platform Live Now. Try Free Answer Evaluation Now

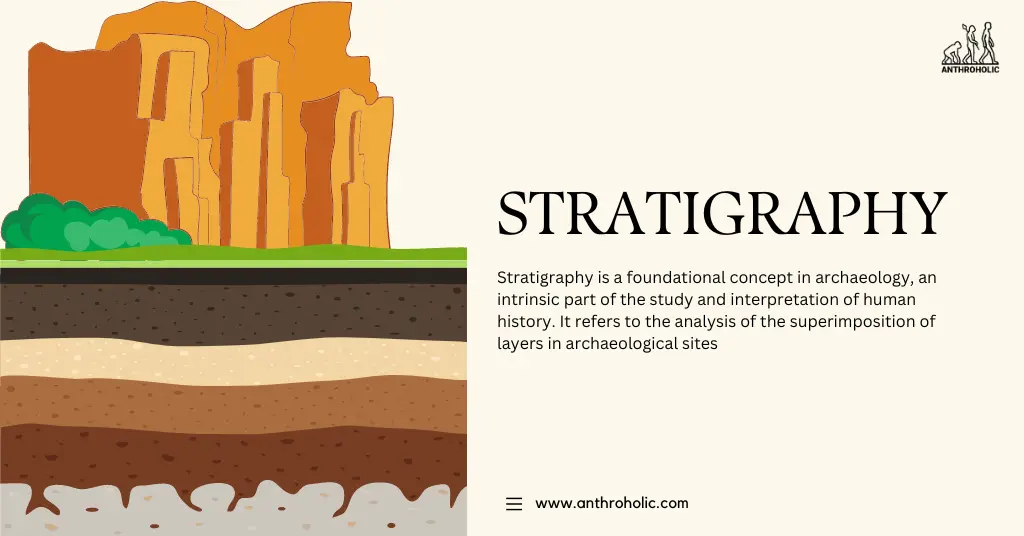

Stratigraphy

Stratigraphy is a foundational concept in archaeology, an intrinsic part of the study and interpretation of human history. It refers to the analysis of the superimposition of layers in archaeological sites [1]. As archaeologists excavate a site, they encounter layers of soil and artifacts which, much like the rings of a tree, help them understand the chronological sequence of historical events [2].

The Principles of Stratigraphy

Stratigraphy operates on three basic principles initially postulated by Nicolaus Steno, a 17th century Danish scientist.

- Principle of Superposition: This principle states that in any sequence of undisturbed strata, the oldest layer is at the bottom and the youngest is at the top [3].

- Principle of Original Horizontality: Steno proposed that layers of sediment are originally deposited horizontally. If strata are found at an angle, it indicates tectonic or other post-depositional activity [4].

- Principle of Lateral Continuity: This principle assumes that layers of sediment extend laterally in all directions until they thin out or encounter a physical barrier [5].

Applications of Stratigraphy

Stratigraphy has proven to be instrumental in various aspects of archaeology:

- Chronological Sequencing: Stratigraphy aids in establishing the relative chronology of archaeological sites. By studying the vertical sequence of layers, archaeologists can deduce the order of events at a site.

- Contextual Understanding: Stratigraphy aids in comprehending the context in which artifacts were deposited. The vertical and horizontal relationships of artifacts and features within the strata can provide insights into past human behavior and environmental conditions.

- Biostratigraphy: Archaeologists use stratigraphy to study changes in animal and plant life over time by examining the fossil content of different layers.

Stratigraphic Techniques

The following techniques are commonly employed in the stratigraphic analysis:

- Stratigraphic Excavation: This involves systematic removal and recording of layers to maintain the sequence of strata for later study.

- Matrix Diagrams: Also known as Harris Matrix, these diagrams visually represent the sequence of strata and their relationships in a site.

- Stratigraphic Correlation: This technique links strata in different locations based on similarities in their physical properties or fossil content.

Limitations of Stratigraphy

Despite its importance, stratigraphy is not without its limitations:

- It does not provide an absolute date; rather it establishes a relative sequence of events.

- Stratigraphic layers may be disturbed by various factors such as animal burrowing, human activity, and geological processes, making interpretation more challenging.

- Not all sediments are deposited uniformly or preserved, leading to incomplete stratigraphic records.

Conclusion

Stratigraphy continues to be an indispensable tool in archaeology. While it has its limitations, the application of complementary dating techniques and meticulous excavation procedures can help mitigate them. Through the interpretation of these layered time capsules, we can continue to decipher the mysteries of our past.

References

[1] Renfrew, C., & Bahn, P. (2012). Archaeology: Theories, Methods, and Practice. Thames & Hudson.

[2] Balme, J., & Paterson, A. (2019). Archaeology in Practice: A Student Guide to Archaeological Analyses. Wiley-Blackwell.

[3] Scarborough, V. L. (2010). The Cambridge World Prehistory. Cambridge University Press.

[4] Stein, J. K. (2001). Exploring Coast Salish Prehistory: The Archaeology of San Juan Island. University of Washington Press.

[5] Roskams, S. (2001). Excavation. Cambridge Manuals in Archaeology, Cambridge University Press.