AI Answer Evaluation Platform Live Now. Try Free Answer Evaluation Now

Chronological Age

Chronological age is an order that has been devised in archaeology, one of which can date different periods with sophisticated chronometric dating technologies like radiocarbon and luminescence. The student would be puzzled as to how archaeologists, say, from the first half of the 20th century, were able to arrange artifacts and places according to chronological order. It is customary for a student of the present to regard prior efforts to impose temporal control as relatively primitive and archaic, considering the large roles that chronometric approaches play in modern archaeology and the apparent precision that they provide. The trouble with this way of thinking is that it fails to consider the fact that early archaeologists established various sophisticated processes for establishing the dates of archaeological occurrences.

Relative dating is a term that is commonly used to define this sort of chronologic control. The trouble with this way of thinking is that it fails to take into account the fact that early archaeologists established a variety of sophisticated processes for establishing the dates of archaeological occurrences. Relative dating is a term that is commonly used to define this sort of chronologic control. The trouble with this way of thinking is that it fails to take into account the fact that early archaeologists established a variety of sophisticated processes for establishing the dates of archaeological occurrences. Relative dating is a term that is commonly used to define this sort of chronologic control.

The trouble with this way of thinking is that it fails to take into account the fact that early archaeologists established a variety of sophisticated processes for establishing the dates of archaeological occurrences. This method is also known as “relative dating.”

How Chronological age is dated?

Relative dating may be used to build a timeline of occurrences without using precise dates or calendar references. Instead of knowing that one sort of pottery was created, say, between 200 and 400 CE and another kind, say, between 500 and 600 CE, all we know is that the later style of pottery is more recent than the first. It is unknown how many hundreds or thousands of years after the first type the second type appeared.

Only one more recent date remains. In a similar vein, we may be able to deduce from historical evidence the final calendrical date of the manufacture and use of the later form of pottery, but we may not be able to determine the exact calendrical date of the type’s introduction and, consequently, the exact date at which it started to replace the earlier variety. Contrarily, absolute-dating procedures, also known as chronometric methods, give a calendar date that, while maintaining within the bounds of sampling error, indicates the time each event occurred and, presumably, its duration, as well as the amount of time that separated each pair of events.

Due to this, absolute dating methods supply data that goes beyond a simple chronological listing, but they in no way supplant relative dating procedures. In certain cases, the latter is better, particularly when searching for vast geographic chronologies. Compared to pricey technologies like radiocarbon dating, which may cost up to $1,000 per sample, relative dating techniques are less expensive. Some of the most cutting-edge research on the subject has gone unreported because so few modern archaeologists have more than a basic familiarity with the early relative-dating approaches. This form of investigation has frequently proved to be effective over time.

A timeline of the era in a Chronological age

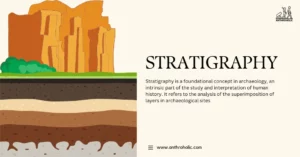

A method employed in archaeology to identify relative temporal orderings is known as stratigraphic excavation; it has its roots in seventeenth-century geological research. Stratigraphic excavation is arguably the most well-known relative dating method employed by prehistorians, given that the majority of the archaeological record has a geological mode of occurrence. Other practices that deserve scrutiny include segregation and cross-dating. All of them, however, are dependent on object categories, especially those that

requirements for historical significance. A type is made up of specimens that were generated during the course of a single, very brief period of time, according to the frequency distribution of the specimens over time, which is comparable to a unimodal curve. A curve of this kind represents the origin of a species, its ascent to prominence, its fall in popularity, and its eventual extinction. Any type that passes the test is a historical type, according to the relative-dating approach, which is the most exact.

Digging in the Stratum: Significant Locations in Chronological age

Lyman and O’Brien defined stratigraphic excavation as the process of recovering artifacts and sediment from three-dimensional, vertically separate units of deposition (strata) and conserving those artifacts in sets in accordance with their independent vertical recovery proveniences[1]. The vertical limits of artifact collecting units may be set using geological standards like sediment texture or metric criteria like height. The primary concept of stratigraphic excavation is that the historical past of strata within a sedimentary column is reflected by their orderly stacking. According to this notion, strata were deposited in a column from top to bottom. The superposition rule applies here.

Unfortunately, archaeologists frequently neglect the premise that the sediments at a site might not be as old as the processes that led to their deposition. Artifacts formed by sedimentary processes are also included in this. Even if some artifacts were deposited in the top layer before others, it cannot be inferred that they are older than those in the lower layers. For instance, it’s possible that erosion from one site transported antiquities from one epoch downslope on top of artifacts from another century.

Superposition in Chronological age

Superposition, an indirect dating technique, may be applied to anything included inside layers. It is indirect since the pieces’ ages may be estimated from their vertical alignments with one another. Or, to put it another way, the target event is the time span in which the artifact was produced, whereas the dated event is the time period in which the deposit was made. Similar to a geologist, an archaeologist must look at superposed sediments to identify when the strata were developed and deposited. Despite the fact that artifacts are frequently found in non-cultural (natural) layers, archaeologists are interested in culturally generated sediments.

When comparing the two, it is generally necessary to grasp the latter’s character. However, trenching operations done by Thomas Jefferson through an earthen mound on his Virginia farm in 1784 are commonly recognised by archaeological historians. It may never be practicable to pinpoint the exact date of the first stratigraphic excavation. The importance of the time-stratigraphic layering’s relevance was then underlined by drawing a parallel between the soil layers and the human remains recovered in the mound. Despite allegations that Jefferson’s work foreshadowed current archaeological practices by a century, Americanist archaeology remained unaltered.

How chronological age is realized by scholars

Sadly, as the British archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler thereafter commented, the embryo of this new scientific capacity was planted on infertile ground[2]. Significant excavations persisted for a century after Jefferson. 75 years later, Great Britain realized Jefferson’s plan with success. Prominent British paleontologists and geologists identified Brixham Cave on the Devonshire Coast in 1858 by putting a strong focus on stratigraphic context. During the second decade of the 20th century, stratigraphic excavation in North America climbed to the level of a stunning art due to the work of two prehistorians from the Robert S. Peabody Museum in Andover, Massachusetts, Alfred V. Kidder and Nelson started his investigation at San Cristobal, an abandoned pueblo in the Galisteo Basin south of Santa Fe, New Mexico, to establish a believable local succession of pottery styles. Nelson stated that at the beginning of the 1914 field season, he had a comprehensive grasp of the historical evolution of five distinct kinds of pottery, two of which had painted designs and three of which had glazed ones.

Due to its abundance on small pre-Puebloan sites, one of the painted forms was assumed to be the earliest of the five. Since it was common in areas where historical records date back to before the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, the second painted style was thought to be the newest of the five. Nelson reasoned that one of the three glazing types was from the early historical period since it was often discovered next to the bones of horses and other historically introduced domestic animals (1540–1680). Between the early painted type and the historical-period glazed type were the other two glazed variants. Nelson said that “strong evidence was still required” notwithstanding his intuitive understanding of the problem. He acquired that evidence at San Cristobal. Instead of working in naturally occurring stratigraphic units, Nelson excavated San Cristobal in artificial, one-foot-thick strata and kept the shards from each level separate.

Analysis of Chronological age through stratigraphy

This aspect of his work has attracted the greatest attention in Americanist archaeological histories. After seeing the stratigraphic excavations carried out in Spain in 1913 by European prehistorians Otto Obermaier and Henri Breuil, Nelson took part in the Castillo Cave excavation. Nelson said that his excavation strategy at San Cristobal was built on this experience. While he used European methods for random level excavation, he rejected the idea that tier collections indicated the passage of time. Everyone agreed on that. Because it revealed how ceramic kinds’ absolute frequencies changed over time in a pattern he called “very nearly normal frequency curves [that] paralleled the fact that a style of pottery grew steadily into favor, attained a maximum, and started a gradual slide,” Nelson’s study was groundbreaking. His categories I through III have continuous distributions in time: they start out, become more and more popular until they reach a peak, at which point they begin to decline, and then they ultimately vanish. Thus, they are particularly beneficial for chronology.

In essence, they serve as magnificent chronometers and produce amazing historical figures. Corrugated pottery is a poor historical category since it does not make use of its pattern. Kidder learned about Nelson’s chronological classification of the ceramic types when he was employed at Pecos Pueblo, which is located immediately to the east of the Galisteo Basin. Kidder chose Pecos as the location for his investigation because historical records showed that the area had been inhabited from 1540 until 1840. Kidder said, “I thought artifacts [in Pecos] would be found so stratified as to make clear the history of the many Pueblo arts and enable children to better understand.” This conclusion was reached as a result of Mr. N. C. Nelson’s recent discovery of extraordinarily huge stratified remains at San Cristobal, a few kilometers to the west.

Arranging Artifacts in Chronological age

Nelson’s chronology, which concluded in 1680 with the abandonment of San Cristobal due to analogous deposits at Pecos, might perhaps be prolonged until the middle of the nineteenth century. Not all excavations at Pecos Pueblo were undertaken with much care for superposition linkages since Kidder noted that the pottery types in the lower layers of his trenches were “markedly different from [those at the top] and that there were several unique sorts between.” Instead, “research done at numerous sites as the excavation progressed” was used to find these relationships. Each tier’s pieces were picked from a different column of trash throughout the test and placed in a different paper bag.

That Kidder paid attention to the stratigraphic origin of the artifacts collected within his false levels is shown by the fact that those tests were conducted during the first field season, which was the summer of 1915, and used artificial levels that were 1 — 1.5 ft deep. But when it was revealed that the arbitrary levels divided visible strata, “a fresh bag was opened” During the first field season, Kidder carefully monitored the visible stratigraphic phases while excavating Pecos Pueblo. In a table, he included details on the relative vertical provenience of various ceramic types, not just their absolute frequency.

Alfred V. Kidder and Nelson Nelson, two prehistorians from the Robert S. Peabody Museum in Andover, Massachusetts, who worked in New Mexico in the second decade of the 20th century, helped stratigraphic excavations in North America mature into fine art. Nelson started his inquiry at San Cristobal, an abandoned pueblo located in the Galisteo Basin south of Santa Fe, New Mexico, to confirm a putative local succession of pottery designs. Before the start of the 1914 field season, there were five distinct forms of pottery, two of which had painted designs and three of which had glazed ones.

In his examination, Nelson asserted that he had a good comprehension of the sequence in which these ceramic shapes first arose. Seriation’s history is as intricate as, if not more so than, any other archaeological approach. Despite the fact that evolutionary seriation was ultimately made available to American archaeologists, it is fundamentally different from the kind of seriation established by Americanists in the second decade of the 20th century. Up until the seventeenth century, evolutionary classification was only used in Britain. Despite this, textbooks typically assume that British archaeologists pioneered seriation.

Seriation in Chronological age

Another particularly American kind of seriation, frequency seriation, promoted the formation of occurrence seriation, another such seriation. Seriation, regardless of how something is organized, is a descriptive strategy that organizes objects in a row or column (in this case, artifact assemblages). A linear order is established through segregation, although this order simply serves to show how two entities are more likely to share qualities when they are close to one another than when they are further up or down the list. Seriation is applied in archaeology for chronological reasons, even if it is inferred rather than overtly stated that an order symbolizes the passage of time. The phrases “seriation” and “percentage stratigraphy” are sometimes used interchangeably, which conflates the two independent processes. John Rowe strongly repudiated the notion of superposed strata in his theory of seriation.

A different logic theory than superposition is applied to structure archaeological remains in a fictitious chronological sequence. The classification is based on the following logical sequence: This idea underscores the impact that the formality of the order’s accompanying paperwork has on the order. Since relative vertical placements in a column of sediments create an exterior characteristic, seriation is dependent on the interior properties of artifacts rather than this outside feature.

In other words, superposition is an indirect dating technique, while succession is a direct one. This method, which is connected to evolutionary seriation, is used by paleontologists to arrange fossils with comparable morphologies in a chronological sequence that allows for a progressive and continuous change in the character states of the fossils. Perhaps the earliest known example of evolutionary segregation is John Evans’ segregation of gold British coins before and after the Roman invasion of Britain in 54 BCE.

Ancient findings in different Chronological age

The most conspicuous grouping of these descendants is the group of vases with wavy handles. They seem to have virtually spherical ledge-handles at first, then upright and smaller, and lastly simply wavy. The handles on early jars, which tended to be enormous and heavy, were initially functional, but with time they grew into aesthetic features and, by the end of the series, decorations, according to Petrie. Petrie came in sixth in 1901. Petrie Seriation in evolutionary terms It was time to arrange the graves according to the many vase types connected with each one once Petrie had figured out the vase sequence.

In addition, some handled-vase types that co-occurred with certain vessel types evolved into their own markers, providing the accurate classification of succeeding burial sites devoid of those particular handled-vase types. Different marker types have been used by archaeologists to achieve the same goal, generally across quite wide geographic regions. A marker type’s lifespan, or temporal length (we pick types with short temporal durations), and geographic distribution (we may choose types that are frequent), dictate how essential it is. In actuality, hardly all archaeologists meet these characteristics.

Without getting into the myriad technical nuances of how types are generated in the first place, let’s simply note that many types have too much variability built into them to work as anything other than fundamental temporal identifiers[3]. The finder commonly wonders, “Is this or is this not an example of that kind?” Sometimes artifact types meet the condition, and as a result, they become reliable marker types that can be used for cross-dating. One such example is the Folsom point, which was used to tip spears in North America between around 8950 and 8500 BCE. Employees of the Colorado Museum of Natural History discovered the find in 1927 when they uncovered six small fluted points and the bones of an extinct bison[4] in an arroyo close to Folsom, New Mexico. For a number of reasons, it has been demonstrated that prior claims that early tools had been unearthed in North America were erroneous.

A stratigraphic connection took place approximately 11,000 years ago in a geological context near the temporal border between the late Pleistocene and the early Holocene epochs. Since stratigraphers were already familiar with how the glacial-age border in the western United States appeared in terms of sediments and layers in the 1920s, the age estimate of the bison-kill site was not an educated guess. The 19 projectile points recovered at Folsom were easy to recognise owing to their attractive flaking and the presence of channel scars, or flutes, generated by removing lengthy flakes on both sides. The Folsom type was rapidly considered a historical monument since its point shape made it hard to mix with more modern forms. The moment a

Eminent developments in the growth of Chronological Age

Similar to many other organizations, the chronological approach has the inclination to pass off work that was completed decades ago as being simple and archaic. Archaeology is an industry where this inclination is especially evident. Some suggest that because radiometric dating has allayed our anxieties regarding chronology, the work of prehistorians like Nelson, Kidder, and Petrie may no longer be of the utmost value. Discussing stratigraphy, seriation, or marker kinds in this case would be pointless. One may make the claim that knowing relative dating is crucial for carrying out excellent archaeological research for two reasons. Priorities first: absolute radiometric techniques do not always address chronological difficulties.

Since relative-dating methods might have considerable repercussions, it is necessary to examine and analyze any information that could be collected from them. Due to the unexpected nature of the processes that are generated and are still forming the archaeological record, radiometric approaches may not always be appropriate. In the second decade of the twentieth century, the nineteenth-century chronology, which had its beginnings in Europe and was predicated on the assumption that artifacts could be used to show the passage of time, reached its height in the American Southwest. Archaeologists may potentially unearth a wealth of information in the investigation’s materials.

References

[1] Lyman, R. Lee, and Michael J. O?Brien. “A History of Normative Theory in Americanist Archaeology.” Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, vol. 11, no. 4, Springer Science and Business Media LLC, Dec. 2004, pp. 369–96. Crossref, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10816-004-1420-6.

[2] Hawkes, Jacquetta. “Mortimer Wheeler.” Adventurer in Archaeology, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1982.

[3] Taylor, R. (2000). Seriation, Stratigraphy, and Index Fossils: The Backbone of Archaeological Dating. Michael J. O’Brien and R. Lee Lyman. 1999. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York, NY. viii 253 pp., 69 figures, bibliography, index. $59.95(cloth), ISBN 0-306-46152-8. American Antiquity, 65(4), 781-783. doi:10.2307/2694446

[4] Bisonantiquus Leidy, 1852