AI Answer Evaluation Platform Live Now. Try Free Answer Evaluation Now

Paleoanthropology

Meaning of Paleoanthropology

Paleoanthropology is a field that studies the evolution, behavior and physical characteristics of prehistoric humans. The discipline is also known as ‘human paleontology’ and is concerned with human fossil record, their location, their origin as well as their identification and classification into the tribe hominidae. Paleoanthropologists focus on assemblages like bones, lithic tools and settlement evidence. The discipline mainly analyzes fossil remains.

In 1891 Paul Topinard first coined the term paleoanthropologie while in the same year, it was introduced into the English language by archaeologist Thomas Wilson.

Paleoanthropology interpolates research from biology, comparative anatomy, paleontology and primate studies.[1]

Before Paleoanthropology

Early Interest

The antiquity of humankind piqued the interests of Greek philosophers and naturalists of the enlightenment age.[2] The literary records from ancient civilizations combined with the interests of modern antiquarians and historians laid the foundation for an inquiry into the human past. The introduction of taxonomy by Linnaeus in 1735 and works by Charles Darwin as well as Lamarck pointed to the idea that humankind has not emerged from a linear evolution nor is it the product of any divine creation.

The Contribution from Geology

On the other hand, geologists like Charles Lyell (Principles of Geology, 1833) and their advances in understanding of stratigraphic layers as indicators of time scales became a key element in this domain. One of the principle tenets of stratigraphy is that the newer material is contained in the top layers while the bottom layers deposit older material. This fundamental aspect allowed geologists to (relatively) date fossils, the layers of strata as well as to study the process of sedimentation. British and French geologists in the nineteenth century came across crude lithic artifacts,mammoth and human bones in geological deposits; this was important in pointing toward a distant past for human species.

A New Perspective

Once these principles of uniformitarianism and evolutionary theory were established, archaeologists could use means of excavation to not only find lithic artifacts but also hominin fossil remains. Following the period of antiquarianism and excavations for museum collections, archeologists began taking interest in human remains and stone tools as means of reconstructing past cultural as well as behavioral inferences.

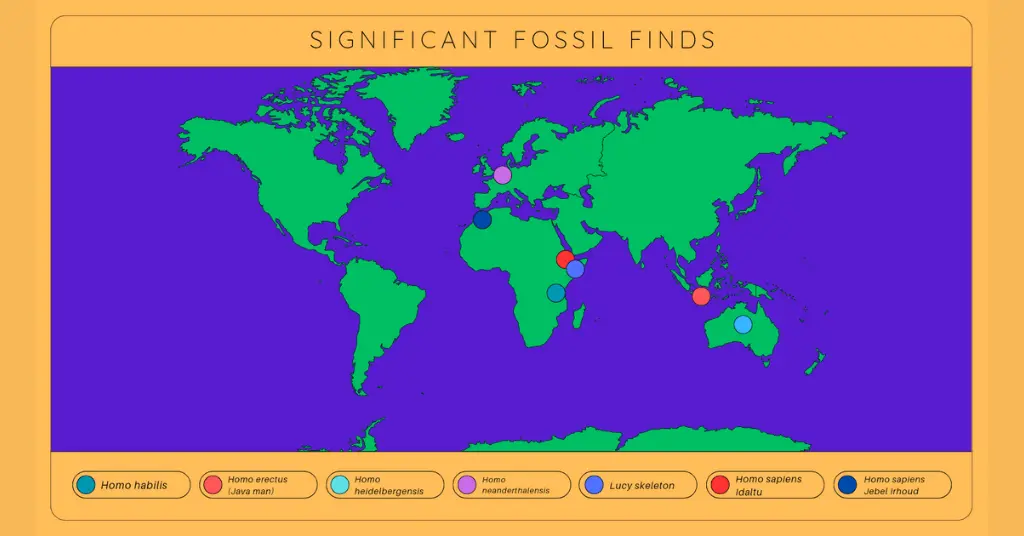

History of Paleoanthropology

In the nineteenth century, while human skeletal finds were not entirely uncommon from neolithic and bronze age tombs, fossil remains from the paleolithic were undiscovered until the evidence of (presumably) Homo neanderthalensis [3] in the Neander valley of Germany in 1856. However, the first intentional fossil excavations are attributed to Eugene Dubois, who in 1890, journeyed to Asia due to the popular belief that life originated there and eventually discovered a skull cap and femur belonging to a bipedal human ancestor in Java, Indonesia.[4] This was later classified as Homo erectus (formerly Pithecanthropus erectus) which lived between 700,000 to 2 million years ago. Other finds in Asia include forty Homo erectus individuals dubbed as ‘Peking Man’ in Zhoukoudian, China which date to 400 kya.

The theory of origin in Asia did not sustain following the discovery of Australopithecus africanus by Raymond Dart in South Africa in 1924, which Dart placed between the anthropoid apes and humans. Subsequently, Louis and Mary Leakey also discovered many fossils and stone tools at the Olduvai gorge in Tanzania. These included the partial cranium of Homo habilis in 1963 which the Leakeys argued was an ancestral species to Homo erectus (due to its appearance in an older deposition but still debatable)[5]. Africa is also home to the famous ‘Lucy skeleton’(Australopithecus afarensis), which was discovered by Donald Johanson in 1973 in the Afar triangle in Ethiopia which was dated to about 3.2 mya. These breakthroughs solidified the potential of Africa as a conducive environment for preservation of fossils and their rich assemblage.

Europe was not exempt from fossil finds. In fact, according to many scholars the discovery of Dmanisi hominins from 1.8 mya in Georgia provides great research on ‘out of Africa’ migrations of Homo erectus.[6] Another notable example from Europe is that of ‘Homo heidelbergensis’ whose jaw was found at Mauer, Germany in 1908.

Modern Paleoanthropology

Paleoanthropology since the 1960s has become an independent discipline of its own. While early scholars came from different backgrounds of study like anthropology, geology and anatomy; researchers today are specifically trained to address paleoanthropological problems.

The story of modern paleoanthropology is best told through the contributions of Tim D. White, who initially worked with Richard Leakey at Koobi Fora, Kenya in the 1970s. However, White has been monumental throughout the 1990s, when his team found the remains of Ardipithecus ramidus; a 4.4 million year-old fossil from the Afar region. This was the first and earliest evidence of pro-social behavior and presumed bipedalism. [7]

The significance of White’s work doesn’t end here. A continued debate in paleoanthropology is regarding the origins of anatomically modern humans (AMH).[8] Initially the oldest known AMH fossil was thought to be the ‘Herto man’ (Homo sapiens idaltu) discovered by White and dated to 160,000 years.[9] Its cranial capacity was 1450, close to modern humans and made use of acheulean tool types.

However, the origin of AMH was pushed back again in 2017.[10] The remains at Jebel Irhoud in Safi, Morocco yielded dates of 300,000 years ago. This was done using thermoluminescence (TL) dating on associated burnt lithic artifacts.

The Process of Paleoanthropology

Paleoanthropology shares aims of research with anthropology and archaeology in the sense that it employs similar techniques to comprehend material and biological remains in order to recreate their contextual pasts. This can include cultural and behavioral patterns of ancestral and contemporary humans. The processes in paleoanthropology require a multifarious scientific research.

Following are the steps of process in paleoanthropology which Tim D. White describes as the ‘Paleo Pipeline’ –

- Identification of fossil localities based on geological data and site surveys. Technology like remote sensing, satellite imagery and aerial surveys can supplement exploration techniques. Additionally, partial remains can be exposed on the surface due to erosion and other natural processes. This helps identify sites with potentiality.

- Recovery of material using excavation methods. This is crucial in palaeoanthropology as fossilized remains can be scattered and disseminated. A variety of sieving methods can help recover these fragments. In-situ deposits can be exposed using hand brush methods.

- Preservation requires using hardening agents like shellac to assure safe collection of fragile finds.

- Cataloging of finds involves data recording and identification. Photography also helps.

- Laboratory analysis is then used for age estimation, classification and archaeometry.

- Modeling can help preserve the finds in silica-based molds and in the 3D-form using computer softwares.

Objectives of Paleoanthropology

Paleoanthropological remains are extremely rare compared to the sheer abundance of lithic tools and artifacts. The fundamental aim of paleoanthropology is to draw a conjecture of the dynamic past (cultures, behavior patterns, subsistence habits) using the static present (fossils, tools).

- Paleoanthropologists aim to classify human fossils and reconstruct the human phylogenetic tree based on excavated remains.

- As seen before, paleoanthropology also helps understand the evolution of ancestral humans by establishing evolutionary relationships based on morphological traits.

- Researchers aim to infer the cranial capacity of past species in order to understand their cognitive capabilities.

- Lithic artifacts found in association with fossil remains give a detailed perspective on tool technology, raw materials and hunting or foraging tendencies.

- Many times, animal fossils are also found alongside human remains. These are identified and examined for cut marks to understand meat eating and butchering practices. Examples include a recent study in Ethiopia which gave such an evidence dating to 3.4 mya.[11]

Conclusion

The article has highlighted the importance and meaning of paleoanthropological research. Emphasis has been given to preceding domains of inquiry to show the transition from antiquarianism to scientifically oriented studies. The significance of the African continent is mentioned as a remarkable place of immense paleoanthropological scope. Lastly, the process, aims and objectives of the discipline elucidate the challenges that paleoanthropologists face.

FAQs related to Paleoanthropology

References

[1] Stanford, C. B., Allen, J. S., & Antón, S. C. (2011). Biological Anthropology: The Natural History of Humankind. Pearson.

[2] Begun, D. R. (Ed.). (2013). A Companion to Paleoanthropology. Wiley.

[3] King, William (1864). “The reputed fossil man of the Neanderthal”. Quarterly Journal of Science. 1: 88–97

[4] Swisher, Carl C. III; Curtis, Garniss H.; Lewin, Roger (2000), Java Man: How Two Geologists Changed Our Understanding of Human Evolution, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-78734-3

[5] Tattersall, I. (2019). “Classification and phylogeny in human evolution”. Ludus Vitalis. 9 (15): 139–140.

[6] CI. Ferring, R.; Oms, O.; Agusti, J.; Berna, F.; Nioradze, M.; Shelia, T.; Tappen, M.; Vekua, A.; Zhvania, D.; Lordkipanidze, D. (2011). “Earliest human occupations at Dmanisi (Georgian Caucasus) dated to 1.85-1.78 Ma”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. doi:10.1073/pnas.1106638108.

[7] White, T. D.; Suwa, G.; Asfaw, B. (1994). “Australopithecus ramidus, a new species of early hominid from Aramis, Ethiopia” (PDF). Nature. 371 (6495): 306–312. Bibcode:1994 Natur.371..306W. doi:10.1038/371306a0.

[8] Relethford, J. Genetic evidence and the modern human origins debate. Heredity 100, 555–563 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/hdy.2008.14

[9] White, Tim D.; Asfaw, B.; DeGusta, D.; Gilbert, H.; Richards, G. D.; Suwa, G.; Howell, F. C. (2003), “Pleistocene Homo sapiens from Middle Awash, Ethiopia”, Nature, 423 (6491): 742–747,

[10] Callaway, Ewan (7 June 2017). “Oldest Homo sapiens fossil claim rewrites our species’ history”. Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2017.22114.

[11] Lovett, R. Butchering dinner 3.4 million years ago. Nature (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/news.2010.399